The Sagrada Familia is a castle built by Australian termites.

The Sagrada Familia is not a castle built by Australian termites, and never will be. Tis utter blasphemy.

The Sagrada Familia is not a castle built by Australian termites, and yet, Look! Notice, as Daniel Dennett bids, how in an untrodden field in Australia there emerged and fell, in near silence, near but for the methodical gnawing, not unlike that of a mouse nibbling rapaciously on parched pasta left uneaten all these years but preserved under the thick dust on the thin cardboard with the thin plastic window enabling her to view what remained after she’d cooked just one serving, with butter, for her son, there emerged and fell, with the sublime transience of Andy Goldsworthy, a neo-Gothic church of organic complexity on par with that imagined by Antoni Gaudí i Cornet, whose Sagrada Familia is scheduled for completion in 2026, a full century after the architect died in a tragic tram crash, distracted by the recent rapture of his prayer.

The Sagrada Familia is not a castle built by Australian termites, and yet, Look! Notice, as Daniel Dennett bids, how in an untrodden field in Australia there emerged and fell a structure so eerily resemblant of the one Antoni Gaudí imagined before he died, neglected like a beggar in his shabby clothes, the doctors unaware they had the chance to save the mind that preempted the fluidity of contemporary parametric architectural design by some 80 odd years, a mind supple like that of Poincaré, singular yet part of a Zeitgeist bent on infusing time into space like sandalwood in oil, inseminating Euclid’s cold geometry with femininity and life, Einstein explaining why Mercury moves retrograde, Gaudí rendering the holy spirit palpable as movement in stone, fractals of repetition and difference giving life to inorganic matter, tension between time and space the nadir of spirituality, as Andrei Tarkovsky went on to explore in his films.

The Sagrada Familia is not a castle built by Australian termites, and yet, Look! Notice, as Daniel Dennett bids, how in an untrodden field in Australia there emerged and fell a structure so eerily resemblant of the one Antoni Gaudí imagined before he died, with the (seemingly crucial) difference that the termites built their temple without blueprints or plan, gnawing away the silence as a collectivity of single stochastic acts which, taken together over time, result in a creation that appears, to our meaning-making minds, to have been created by an intelligent designer, this termite Sagrada Familia a marvelous instance of what Dennett calls Darwin’s strange inversion of reasoning, an inversion that admits to the possibility that absolute ignorance can serve as master artificer, that IN ORDER TO MAKE A PERFECT AND BEAUTIFUL MACHINE, IT IS NOT REQUISITE TO KNOW HOW TO MAKE IT*, that structures might emerge from the local activity of multiple parts, amino acids folding into proteins, bees flying into swarms, bumper-to-bumper traffic suddenly flowing freely, these complex release valves seeming like magic to the linear perspective of our linear minds.

The Sagrada Familia is not a castle built by Australian termites, and yet, the eerie resemblance between the termite and the tourist Sagrada Familias serves as a wonderful example to anchor a very important cultural question as we move into an age of post-intelligent design, where the technologies we create exhibit competence without comprehension, diagnosing lungs as cancerous or declaring that individuals merit a mortgage or recommending that a young woman would be a good fit for a role on a software engineering team or getting better and better at Go by playing millions of games against itself in a schizophrenic twist resemblant of the pristine pathos of Stephan Zweig, one’s own mind an asylum of exiled excellence during the travesty of the second world war, why, we’ve come full circle and stand here at a crossroads, bidden by a force we ourselves created to accept the creative potential of Lucretius’ swerve, to kneel at the altar of randomness, to appreciate that computational power is not just about shuffling 1s and 0s with speed but shuffling them fast enough to enable a tiny swerve to result in wondrous capabilities, and to watch as, perhaps tragically, we apply a framework built for intelligent design onto a Darwinian architecture, clipping the wings of stochastic potential, working to wrangle our gnawing termites into a straight jacket of cause, while the systems beating Atari, by no act of strategic foresight but by the blunt speed of iteration, make a move so strange and so outside the realm of verisimilitude that, as Kasparov succumbing to Deep Blue, we misinterpret a bug for brilliance.

The Sagrada Familia is not a castle built by Australian termites, and yet, it seems plausible that Gaudí would have reveled in the eerie resemblance between a castle built by so many gnawing termites and the temple Josep Maria Bocabella i Verdaguer, a bookseller with a popular fundamentalist newspaper, “the kind that reminded everybody that their misery was punishment for their sins,”**commissioned him to build.

Or would he? Gaudí was deeply Catholic. He genuflected at the temple of nature, seeing divine inspiration in the hexagons of honeycombs, imagining the columns of the Sagrada Familia to lean, buttresses, as symbols of the divine trilogy of the father (the vertical axis), son (the horizontal axis), and holy spirit (the vertical meeting the horizontal in crux of the diagonal). His creativity, therefore, always stemmed from something more than intelligent design, stood as an act of creative prayer to render homage to God the creator by creating an edifice that transformed, in fractals of repetition in difference, inert stone into movement and life.

The Sagrada Familia is not a castle built by Australian termites, and yet, the termite Sagrada Familia actually exists as a complete artifact, its essence revealed to the world rather than being stuck in unfinished potential. And yet, while we wait in joyful hope for its imminent completion, this unfinished, 144-year-long architectural project has already impacted so many other architects, from Frank Gehry to Zaha Hadid. This unfinished vision, this scaffold, has launched a thousand ships of beauty in so many other places, changing the skylines of Bilbao and Los Angeles and Hong Kong. Perhaps, then, the legacy of the Sagrada Family is more like that of Jodorowsky’s Dune, an unfinished film that, even from its place of stunted potential, changed the history of cinema. Perhaps, then, the neglect the doctors showed to Gaudí, the bearded beggar distracted by his act of prayer, was one of those critical swerves in history. Perhaps, had Gaudí lived to finish his work, architects during the century wouldn’t have been as puzzled by the parametric requirements of his curves and the building wouldn’t have gained the puzzling aura it gleans to this day. Perhaps, no matter how hard we try to celebrate and accept the immense potential of stochasticity, we will always be makers of meaning, finders of cause, interpreters needing narrative to live grounded in our world. And then again, perhaps not.

The Sagrada Familia is not a castle built by Australian termites. The termites don’t care either way. They’ll still construct their own Sagrada Familia.

The Sagrada Familia is a castle built by Australian termites. How wondrous. How essential must be these shapes and forms.

The Sagrada Familia is a castle built by Australian termites. It is also an unfinished neo-Gothic church in Barcelona, Spain. Please, terrorists, please don’t destroy this temple of unfinished potential, this monad brimming the history of the world, each turn, each swerve a pivot down a different section of the encyclopedia, coming full circle in its web of knowledge, imagination, and grace.

The Sagrada Familia is a castle built by Australian termites. We’ll never know what Gaudí would have thought about the termite castle. All we have are the relics of his Poincaréan curves, and fish lamps to illuminate our future.

*Dennett reads these words, penned in 1868 by Robert Beverley MacKenzie, with pedantic panache, commenting that the capital letters were in the original.

**Much in this post was inspired by Roman Mars’ awesome 99% Invisible podcast about the Sagrada Familia, which features the quotation about Bocabella’s newspaper.

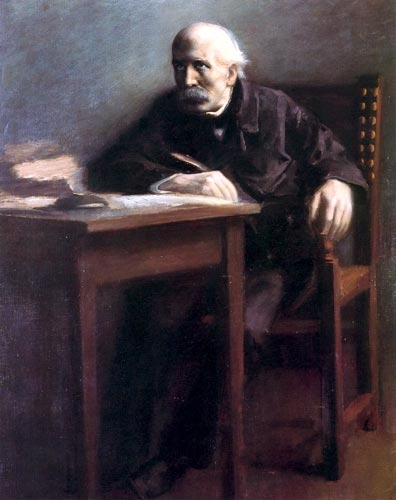

The featured image comes from Daniel Dennett’s From Bacteria to Bach and Back. I had the immense pleasure of interviewing Dan on the In Context podcast, where we discuss many of the ideas that appear in this post, just in a much more cogent form.

One thought on “Clinamen”