“In the seventh century,” writes Lewis Mumford in Technics & Civilization, “by a bull of Pope Sabinianus, it was decreed that the bells of the monastery be rung seven times in the twenty-fours hours. These punctuation marks in the day were known as the canonical hours, and some means of keeping count of them and ensuring their regular repetition became necessary.” The instrument that would help the monasteries ring bells on a regular basis was the mechanical clock, whose “‘product’ is seconds and minutes.” Standard, measurable sequences of time not a latent property of the universe, but the output of a man-made machine. Mumford proposes that the monastic desire for order, the desire to cultivate a way of being where surprise, doubt, caprice and regularity were put at bay, was the cultural foundation that created the clock, but that the clock went on to “give human enterprise the regular collective beat and rhythm of the machine; for the clock is not merely a means of keeping track of hours, but of synchronizing the actions of men.”

This effect continues to impact us today. Most of us structure our existence by the synchrony of the industrial work week, waking up Monday through Friday at a certain time, commuting on crowded trains or highways with everyone else at a certain time, breaking for lunch at a certain time, showing up to meetings punctually and ordering the exchange of information and ideas to fit a pre-determined 30 or 60 minutes (the skill of managing meetings to maximize communicative efficacy a byproduct of the need to keep time), coveting weekends or vacations because we crave a moment of unstructured respite, crave the opportunity to vaunt our enlightened ability to take a device-free day (so we can return fresher and more productive on Monday), all-the-while watching Monday peer over the horizon and looking forward, once more, to the following Friday at 5:00 pm.

Perhaps more profoundly (or perhaps as a byproduct of the way we live day to day), we continue to share the assumption that time working normally is time that flows at the same, standard pace for all individuals and for the same individual at different periods in their life. I infer that this is a standard assumption because of how much it interests us to explore the contrary, namely that our subjective experience of time is not standard, that you might think our activity dragged on for hours while I thought it flashed by in seconds, that time from our childhood seemed to pass so much more slowly than it does in old age.

At 35, I cannot give a rich, inner account of what time feels like for a 70-year-old or 80-year-old. But over the past few weeks, I asked a handful of people 70 and above to describe their experience of time and account for why they think time feels faster as they get older. What follows are four accounts for why time speeds up as we age and a few suggestions for things we can do to slow time down. I take it for granted that slowing down time increases our sensation of living a meaningful life. For there is power in the continuum: if there’s an upper bound on the number of years we can live, why not focus on expanding our perception of the duration of each year, of each instant? At the theoretical limit, we would achieve immortality in a moment of living (an existentialist take on Zeno’s paradox, which any good pragmatist should and could easily shut down, and which Jorge Luis Borges elegantly explored in the Secret Miracle).

Why Does Time Speed Up as We Age?

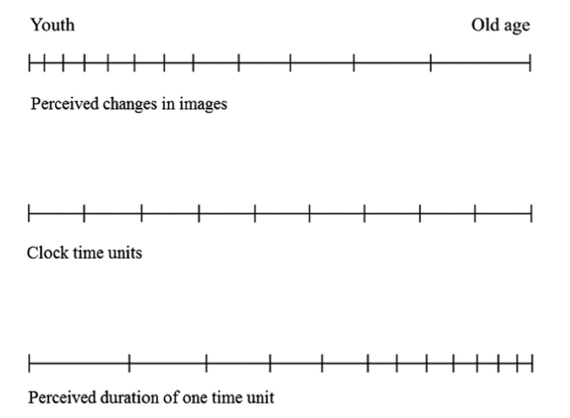

Let’s start with a physics argument proposed by Duke professor Adrian Bejan. In his short article Why the Days Seem Shorter as We Get Older, Bejan focuses on how the structure of the eye changes with age, lengthening the periods between which we can perceive a change in a succession of images, i.e., can experience a unit of time:

Time represents perceived changes in stimuli (observed facts), such as visual images. The human mind perceives reality (nature, physics) through images that occur as visual inputs reach the cortex. The mind senses ‘time change’ when the perceived image changes…The sensory inputs that travel into the human body to become mental images-‘reflections’ of reality in the human mind-are intermittent. They occur at certain time intervals (t1), and must travel the body length scale (L) with a certain speed (V)…L increases with age because the complexity of the flow path needed by one signal to reach one point on the cortex increases as the brain grows and the complexity of [path flows in the eye] increases…At the same time, V decreases because of the aging (degradation) of the flow paths. Two conclusions follow: (i) More recorded mental images should be from youth and (ii) The ‘speed’ of time perceived by the human mind should increase over life.

So, essentially, because we perceive fewer changes in images as we get older, time seems to flow more quickly.

Neuroscientist David Eagleman makes a similar argument with different rationale. Eagleman builds on experiments where people are shown images of cats, each image for 0.5 seconds. Experiment participants are presented with an image of the same cat multiple times, and then presented with an image of a different cat: results show that participants feel like the new cat is on the screen for a longer period of time (even though all images are presented for only 0.5 seconds). Eagleman’s conclusion is that “when the brain sees something that’s novel, it has to burn more energy to represent it, because it wasn’t expecting it. The feeling that things are going in slow motion is a trick of memory.” As children, he continues, we are constantly bombarded by novelty as we work to figure out the rules of the world and, importantly, write down a lot of memory. By contrast, in old age we sink into routines and habits, and no longer need to sample as much from the world to navigate it. Because we perceive less, we remember less, and looking back on the past year it seems to have flown by. Note the mechanisms accounting for time speeding up differ slightly from those provided by Bejan: Eagleman includes the mechanisms of expectation and memory, of our brain’s models of the world as the core explanation for why we seem to be taking in and recording less data from the environment we inhabit. Similar between the two, however, is that these mechanisms occur beyond the horizon of our own conscious perception-they happen without our knowing it or being able to describe the experience.

When I asked people in their 70s and 80s how time feels as they age, they all reported it seems to go by faster, but focused their explanations on higher-level relative experience.

Men tended to focus on the relative length of one day’s existence vis-a-vis the total amount of time they’d lived or the total amount of time they presumed they had left to live. So, if you’ve only lived 365 days, each day is 1/365th of your total existence; if you’ve lived 27,375 days (75 years old), each day is 1/27,375th of your total existence. As a much smaller percentage of your total lived experience it will feel like the day passes more quickly. The converse is the sense that there are fewer years left to live, as well as the increasing awareness of the inevitability and proximity of death. Here, each day feels more important, as there are only so many more to live. The subjective experience of time feels faster because it is more precious.

Women tended to focus on the perception of how quickly younger people (i.e., grandchildren) in their lives change. We grow and learn quickly as children (and sometimes as adults), but inhabiting our own consciousness, aren’t (often or always) observing ourselves in time-lapse. The changes occur quickly but nonetheless gradually and continuously, and absent epiphany we don’t factor our own change into our perception of time. But many grandparents, especially in North America, don’t see their grandchildren on a daily basis. They can observe massive week by week, or month by month, or year by year changes, which occur much faster than the sameness they perceive in their own minds, bodies, and existences. It was interesting to me that women focused more on their experience of others, that their very notion of time was relative to how they experience others. I don’t want to claim gender essentialism, and am sure there are men out there who would also focus their sense of time on changes they see in others. But this was what I found in my small interview sample.

How Can We Slow Down Time?

As mentioned above, I’m going to take for granted that we’d want to slow down time to live a richer and more meaningful life (rather than wanting time to speed up as we age to just get things over with). Here are a few ideas on things on to make that happen:

- Introduce novelty into daily life - In the video above, Eagleman references activities as simple as brushing our teeth with the opposite hand or wearing our watch on the opposite hand. Various small actions we can take to break mundane habits that nonetheless force the brain to do more work than it normally does. An extreme example would be learning to ride a bike whose handles steer the wheel in the opposite direction we learned originally.

- Travel - There’s a banal account of travel that would focus on seeing a new culture and exploring an environment different from the one we see every day. Another take on novelty. But I think the impact on travel can be much more profound. First, it’s an opportunity to consciously activate more of our senses than we pay attention to in our daily lives. I’m against the idea that viewing an image of a foreign place or experiencing it through virtual reality is enough to satisfy our craving to experience that new place. This betokens a focus on sight as the primary sense for knowledge, forgetting the importance of sound, smell, touch, and taste. When I visited Bangalore and Madurai, India, I was constantly amazed by the extreme juxtaposition of smells on the streets, where one second’s sensation of exhaust and filth would be followed by the second’s of jasmine whiffs from the woven necklaces at a small street stand. These smells oriented my sense of space, oriented what I saw around me and shaped my memories of the experience. Second, some of the most profound memories I have of time dilated almost to a standstill have been while traveling alone. Living outside any social connections and pressures, abstracted from my past as from my future to focus on the gait of passersby, of the tiredness I sense in my legs on day three after walking around cities or mountains to take in sights, on sensing aloneness without feeling the pangs of loneliness that one feels ensconced in a social context. Everything is heightened, even if I wish I had the opportunity to share what I’m experiencing with others. This isn’t just about novelty; it’s about providing a context to practice sensing more from the surrounding environment, without the myopia of driving an outcome or goal.

- Do one thing at a time - This as living mindfully. Not just meditating 20 minutes per day, but doing daily activities in a mindful way. One of the hardest is to eat without doing anything else. I don’t mean focusing on the social bond created by sharing a meal with others. I mean eating by oneself without reading something or writing an email or watching TV or doing something else while eating. Just focusing on taste, texture, how long the food stays in the mouth before swallowing, what the plating looks like, what the colors look like, how it tastes to combine two things together (or whether it’s cleaner to keep them separate), what the temperature is like on tongue or lips or cheeks or glasses, what a utensil looks like as it interacts with food (like a spoon going in and out of soup), how the body’s sensations change during the meal. Eating is a good starting point that could serve as a practice ground for many other simple activities in life: walking, reading (without getting distracted by the internet), nursing a baby, caring for a sick person, sitting and breathing.

- Enliven the present through analogy and memory - I recently read The Art of Living, which Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh wrote at the age of 91. In one passage, Nhat Hanh shows how “ten minutes is a lot of a little [depending] on how we live them.” He goes on to describe how, when preparing for a talk, he “opened the faucet a little sot hat only a few drops came out, one by one.” He then imagined these icy drops as melted snow falling in his hand, which transported him back to memories of the Himalayan mountains he’d experienced in his youth, far away now that he was in a hut in a monastery in France. He then abided in the metaphor, seeing dew on the grasses he passed outside as he walked to his talk as more drops of Himalayan snow, seeing the water on his face and in his body as connected to this Himalayan snow. His account is interesting because it skirts how we normally think about mindfulness. This wasn’t about focusing attention to observe what’s there, but about hopping from one analogical connection to another to bring out unity in experience. Key, of course, was that he wasn’t focused on what came next, wasn’t anxious about what others would think about him when he gave his upcoming talk. He dilated a few drops of water into a grand theory of interconnectedness, traveling through the vehicle of his own associations and memories. As we age, we carry with us this lapsed time, these lapsed experiences. It may be that it’s how we relate to our own past that is the secret for how we expand the meaning of our present.

Conclusion

This post was primarily about sharing thoughts I’ve had over the past few weeks. The real significance is to try to recover the habit of writing regularly, a habit which has dwindled over the past year. One must start somewhere. I’ve always found that a regular writing practice expands what I perceive around me, as I feel motivated to capture as much as possible as material for what I’ll write. Perhaps that’s the dual significance of this post.

The featured image was taken at sunset in Grenadier Pond in High Park in Toronto in December, 2019. Mihnea and I were on an evening walk. The sun grew as it capped the horizon, pitching grass tufts into relief. A few people walked by with dogs; a woman insisted we walk further south to catch this beauty in a thick French accent. Time slowed as we focused on the changing hue of the grass tufts, which became darker at their center and lighter around the edges.

Reblogged this on The Wombwell Rainbow and commented:

Intriguing read

LikeLike

Ha! I just posted about this and, exactly as you say, my long-time theory was that it had to do with the fraction of my lifetime one year was at, say, 10 compared to 60-mumble. Discussing this with a friend, her theory was about how adults have constant worries and anxieties — the same old, same old — whereas children are more carefree.

I do suspect the main reason, though, is our aging brains slowing down. I know mine has!

LikeLike