A literary experiment in the style of the first two volumes of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s Seasons Quartet. As Knausgaard wrote Autumn and Winter waiting for his daughter Anne to be born, so I write this post waiting for my son Felix, who could come any day now.

Yesterday around 11:40 am Mihnea and I went to Big Wax car wash at Parliament and Front Street in Toronto. There was a medium-long line, but it wasn’t nearly as long as the one we left in exasperation the day before at an Esso automatic car wash closer to our home. There it seemed like everyone in Toronto washed their car at the same place and at the same time on a Saturday afternoon. Urban rituals, tucked into life like the starched collared shirts that pixelate the PATH conjoining the Toronto banks with prepared foods from McEwan’s restaurants and grocery stores. The line at Big Wax moved fast because the car wash staff moved fast. The process started with a man who walked car by car to take people’s orders in intermittent lulls from his primary work spraying down cars before the main wash. His thick brown eyebrows furrowed under brown hair and eyes in discipline, his gaze never landing anywhere but remaining aloof, absent, focused, leaving just enough space to take in the eccentricities and emotionality of the clientele like a data stream, but never stopping long enough to absorb them. On his carbonless copy paper pad, he checked off whether the customer wanted an $11.75 Rinse and Dry or a $14.95 Rinse and Shine or a $26.00 Big Wax complete job, the whole works, including interior cleaning. Didn’t chit chat. Checked the box, placed the yellow sheet on the dashboard and handed the white sheet for payment to Mihnea, moved on to the next car, eventually pivoted back to the front of the line to spray the next car and keep things moving. We inched our way to the front of the line. Our wheels were cockeyed and another staff member gestured vigorously through the closed windows to get us to move them straight so they would settle into the ruts that would pull the car through the wash. Inside the car we shuffled through my Spotify Discover Weekly, largely disappointed by the recommended music. Most of my time listening to music is spent at work, and most of the work music does for me is to block out the noise of the open concept office spaces I inhabit so I can concentrate. I favor minimal ambient music like Brian Eno’s Thursday Afternoon or any track on Jónsi’s Riceboy Sleeps or Max Richter’s Recomposed by Max Richter: Vivaldi’s Four Seasons or other Scandinavian and Icelandic minimalist and post-rock composers like Ólafur Arnalds and Jóhann Jóhannsson and Arvo Pärt (admittedly somewhat different). Too much melodic structure distracts me; words distract me; but the rich symphonic interplay of minimalist rhythms and melodies keeps me cradled, protected, focused even when others bang keys or eat carrots or speak about something I’d have to pretend not to want to overhear. The problem is that the latent representation guiding the Spotify recommender system frequently mistakes my taste in minimalist ambient music for a taste in massage-table easy-listening piano music. This week’s recommendations largely sucked. I pressed the “don’t like this song” icon again and again, cycling exasperation until we landed into a rich tapestry of a Jónsi song as we put the car into neutral to begin our journey in the underworld of the automatic car wash.

Going through a car wash is like being in a whale’s stomach, or being on a roller coaster in a broken-down amusement park in North Korea. All control over the vehicle and experience is handed over to the rails of the machine, which lugs the car in incremental steps. Soapy water gushes around the windshield like saliva, bright red tongues lash and lap suds as if they were breaking down prey flesh. The tongues thud against the steel and glass of the car, not so hard that it’s worrisome but hard enough that it’s a distinctive thud. After red comes blue as the light dims in the center of the wash’s belly. The cadence of swishing and swooshing changes as salt and mud and dirt and winter muck falls off the car onto the ground below, in through ducks into the ground. The car moves on to the next station. Felt fabric organs close in once more over the windshield. Inside the car is warm and dry. Eyes watch awestruck, ears hear the nuances between each phase. Light emerges again near the exit and a massive dryer descends from the ceiling, its air spewing water droplets from the windshield with a force much greater than the hand dryers in public bathrooms, but similar. If the dryer were to have direct contact with faces inside the car, lips would stretch like a skydivers. The whole thing lasts about five minutes.

The experience of the car wash hasn’t changed at all since I was a kid. When I was in elementary school, we lived on Highland Drive in Apalachin, New York, and would go to the car wash every few weeks just past Hidy Ochiai’s Karate studio on the Vestal Parkway. I wanted to go, loved going, and suspect my brother did too. It’s easy to understand why the car wash would be such a treat: the experience is radical, bizarre, otherworldly. In my memory we pulled up to an automated menu similar to the interface at a fast food drive-in. I don’t think, in reality, the car wash menu visual design was anything like images of a Big Mac or Chicken McNuggets. It was probably a simple pick list in primary colors like Mihnea and I saw yesterday at Big Wax. I suspect my memory tricks me because the drive-thru feels similar to the car wash; we wait in the car for a service, and select from a menu along the way. I haven’t eaten drive-thru food since I was a kid. And I believe yesterday was the first time I went through an automatic car wash since we lived in Apalachin. Part of me thinks that can’t be true, that I must have experienced a car wash during my teens in the Boston suburbs. I didn’t own a car for much of my adult life, as I lived in urban downtown cores and moved around using public transportation (and barely cared for the busted Suzuki Forenza I drove around the Bay Area during graduate school; at any rate, cars rarely need washing in Palo Alto). But it’s also possible that yesterday my mood and mindset was open and imaginative enough to elide more with the joy I experienced at the car wash as a child. That the harmonic overtones the experience evoked took me back to the car wash experience of my 7- or 8-year-old self, absorbed in the oddity, not distracted by the self-absorbed tribulations of my 14- or 15-year-old self. Perhaps.

In late November, on our way home from the ritualistic Thanksgiving trip to my aunt’s house in Scranton, Pennsylvania, Mihnea and I stopped in Apalachin so I could show him the house I grew up in. Here it is, at the corner of Highland Drive and Alpine Drive.

It hasn’t changed drastically, although there are differences. I don’t think we ever had a yellow door. We used to have a big crab apple tree in the front yard and a willow tree on the side near the two windows visible in the photo near the chimney. Those were windows into my childhood bedroom, and I spoke to the willow tree like a friend until we tore it down in the wake of a hurricane. When we visited in November, I stood on the driveway and looked up the street. It felt the same. I could see the Valentas’ house and see the Batman Boomerang I once accidentally threw into a friend’s forehead. I looked down the street and it felt different. The Yonkos’ home seemed to sit at a different angle than I remembered, the proportions were off. I could see my brother getting hives from eating huckleberries at the house across from the Yonkos’ down the road. Mihnea and I walked up the hill and down another hill to Tioga Hills Elementary School. The walk was shorter than I remembered from my childhood, when my hair tips used to freeze, still wet from the shower. We walked behind the school and, for the first time in 20 years, I remembered what it felt like to play wall ball with the boys, remembered feeling invited by them because I was athletic, but already embarrassed in budding self-awareness. As we looped around the front of the school, I remembered the day, in fifth grade, when I wore my new Limited cut off jean shorts and Limited bright pink and yellow sleeveless plaid shirt, which I wrapped up near my waist like an aerobics instructor in the early 90s. I was freezing, and one of my teachers asked me why I thought it was a sound idea to wear an outfit like that when it was still so cold. The forecast predicted 62 degrees fahrenheit; I was excited for the warmth of spring, but hadn’t yet realized a daily high could be but a moment in time. I don’t think I got sick, but I shivered most of the day. After seeing the house, Mihnea and I ate at the Blue Dolphin Diner, where we ate frequently when I was a child. They served the same homemade white bread loaves: square loafs that came with a serrated knife and little whipped butter packets. We sat at the bar. When I was a kid, we sat in the main dining room. I ate a Greek combo plate with moussaka and hot dolma and a greek salad with canned black olives and pepperoncini and iceberg lettuce. I could barely eat half before I was stuffed. Mihnea had a Ruben and crinkle-cut french fries. When I was a kid, I used to eat the baked ziti. My mother would warn that the man was coming if my brother and I acted up.

Yesterday, after the huge dryers blew most of the water off the car, we pulled up outside and two more staff members came to do the final hand dry with long, thin, light-blue towels. Mihnea got out to pay the bill, and I was alone inside listening to the one salvageable track from my Discover Weekly List. The guy drying the car asked me if he could come in a pull it forward to make more space for the next car. I said sure. Upon getting in and seeing my 36-week-pregnant belly underneath a sloppy grey sweatshirt he exclaimed “well look at you!” And he warmed up. Like many strangers do these days. Being pregnant is like being a dog: people smile at me and greet me and seem to presume innocence.

“Boy or girl?” he asked.

“Boy,” I replied.

“I have two. It’s going to change your life. But for the better. You will love it.”

I smiled. “I think so too.”

He finished his work and left the car. But my view of him and his view of me changed. It wasn’t just a transaction, wasn’t just aloof eyes pushing the cars through the car wash. I heard the brightness of his voice and knew slightly more about the facts of his existence, rather than speculating about his life outside the car wash. He had two boys. We shared something fundamental. I wonder if his boys think the car wash is as strange and magical as I do, as I suspect Felix will.

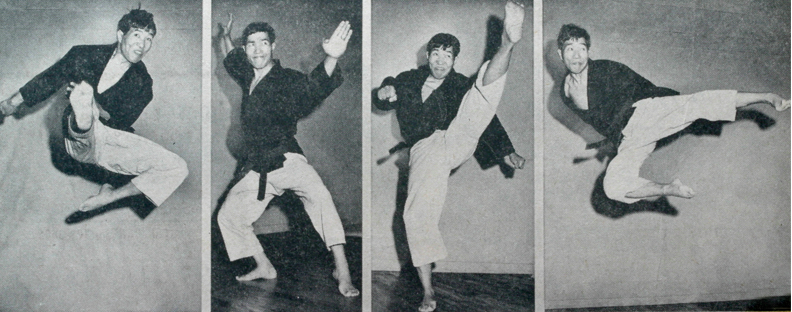

The featured image has nothing to do with a car wash, besides the metaphorical similarity of salt clinging on the sides of cars in winter like barnacles and shells clinging to metal fences near the lake. The mood of the image better matched the mood and tone of the piece than any images I could find of automatic car wash brushes.