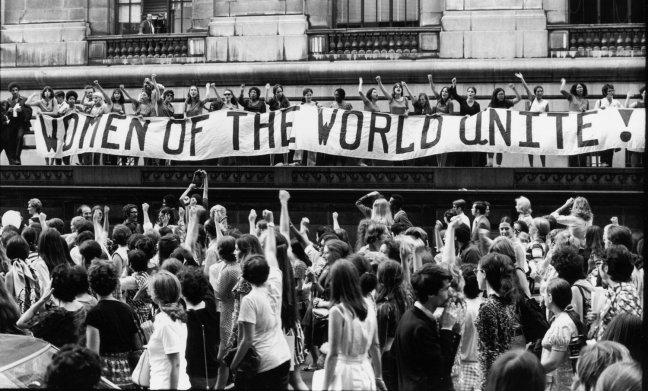

On January 21, women marched on Washington. They marched on New York City. On Seattle. On San Jose. On Antarctica. On Auckland. On Kolkata. 4,956,422 women and men marched in 673 locations. The energy across social media was contagious and powerful, at least inside the liberal and progressive continent of the internet I inhabit.

On January 22, I drafted a blog post articulating what I think it means to champion women’s rights. To amplify rhetorical impact, I used general, normative statements: “Women should have reproductive rights. They should have the right to use birth control and have a legal and safe abortion. They should…” I didn’t have time to finish the post, but showed the draft to my partner. His primary critique was that I - falsely and perhaps offensively - made it seem like my particular experience holds - or, even worse, should hold - for all women, that my way of being in the world was the way all women should be in the world.

That’s the opposite of what I wanted to communicate. Indeed, for me, to champion women’s rights is to champion human rights. It is to champion tolerance. To champion freedom to be oneself and express oneself, the freedom to think, question, create, and criticize. To champion the mental and spiritual work required to deeply accept alterity and difference, to endorse and cultivate the skills of citizenship and democracy. And not just in the realm of discourse, but in the realm of intimacy and action. To go to places that create discomfort and abide in those places, normalizing the difference, truly absorbing a worldview that, a termite, nibbles away at the foundations and security of what we once believed. This, for me, is the essence of what millions of people marched for on January 21. Maybe it’s called empathy with a generous dose of reflection.

So much has happened since then. Just yesterday, I introduced a brilliant, capable, female Muslim data scientist to an entrepreneur in Toronto. President Trump’s Executive Order has pushed her out of the United States. I hope she will prosper in a country more accepting of her talents.

I find it difficult to write in these turbulent times because it feels immoral to write about anything but the most pressing issue of the day. Should I write about immigrant rights? Should I write about the Yemeni bodega strike I experienced Thursday night on my way home from work? Or should I insulate my writing from politics and allow myself to explore humanistic aspects of artificial intelligence, my current professional focus? The imperative to write about social and political issues stems in great part from the ostracism I imagine I’d experience if I were to write about something technical and abstract at this critical moment in history. And this very imperative, as it happens, is at the heart of the one branch of the ethics of artificial intelligence. I’ll write an in-depth post on this soon, but for now suffice it to say that I agree with Joanna Bryson that “pain, suffering, and concern for social status are things essential to a social species, and as such they are integral to our intelligence.” No matter how intelligent they get, AIs will not suffer from social exclusion like we do. There’s a lot to that.

Circling back to women’s rights, I would like to sketch one particular take on feminine identity. It is my take, shaped by my experiences. It will resonate with some and offend others. I accept that. It’s all I can give.

A woman, I should have reproductive rights. I should have the right to use birth control and have a legal and safe abortion. This is important so that motherhood is an active choice, so that I am in a position to raise my children fitfully, responsibly, joyfully, and to the best of my abilities. As such, this is more my child’s right to the best life possible than my own right to use my body as I like.

A woman, I should have the right to excel in my career. I work in business and strive to be CEO of a tech company in the future. Were I in politics, I would want the right to be president (naturally only after meriting the role by busting my ass for years and years to understand the astounding complexity of domestic and international affairs). Were I a stay-at-home mom, I would want the right to be a mom, to take pride raising my children to become awesome people and citizens, like the Abigail Adamses of the early American Republic.

A woman, I should have the right to be treated and seen without gender in some social contexts and with gender in other social contexts. Negotiating with men in suits at hedge funds and Wall Street banks, I would like to be seen as a man in a suit; not even as a man, but as a rational vessel executing a function. A business brain in a vat. In other contexts, I would like the right to embody my femininity, to feel myself as beautiful, to know the timber in my voice, to deliberately craft elegance in my gestures, and to have this unashamedly be part of who I am. I do not believe there need be blanket systematicity to gender or feminism. As with many other aspects of modern, secular identity, gender itself can be latent or activated accordingly to context.

A woman, I should have the right to embrace my professional identity in sales and marketing without the branded (as in scarlet letter) shame that these are roles more often occupied by women. Most “women in tech” energy is devoted to technical roles (think Grace Hopper). I think that’s great, and certainly lament how few women I see at highly technical security or engineering conferences. What I don’t think is great constantly being treated as a second-class citizen just because I do not spend my days coding. I love math. I love geeking out on the details of how software works. I love statistical models, and love how satisfying it is to learn how much more there is to learn every day. But I also love leading a life of action and interaction. Meeting people every day, encountering curious folks and territorial folks, listening to them, asking them questions, and finding a way to make technology valuable and interesting for both their company and their personal ambitions within their company. I should have the right to see value in the task of building bridges between technical and non-technical communities, in ushering technology from academic experiment to impactful commercial product. As I explored in my dissertation, there is a difference between l’esprit géométrique (slow, logical-deductive thinking in math proofs) and l’esprit de finesse (quick, synthetic judgments in response to unanticipated information in social contact). Doing sales and marketing well requires both. Left-brain, right-brain stuff. I’m tired of getting slack for allowing myself to feel alive.

A woman, I should have the right to understand and accept the lifestyles and practices of other women who live radically differently than I. Saba Mahmood’s Politics of Piety helped me appreciate how, counter to our Western Liberal Mindset, female Islamic dress and practices can actually be lived as empowering expressions of self-worth and piety, not enslaving repression. My dear friend Gillian Power recently became woman after spending 40 years trapped in her male body. Post transition, she and her wife continue to raise their two cherubic daughters. I will never exactly appreciate the fear Gillian felt when she wrote her coming out letter to the management of her conservative law firm. But I read the drafts, and, having myself suffered from alienation and fear of judgment, felt deep joy in being part of the circle that enabled her to come more fully into herself.

There are other rights women should have. Expressing any of this is delicate, as it exposes deeper aspects of self than those I normally reveal in the safe, abstract space of math and technology. As with everything else on this blog, it’s as near as may be.