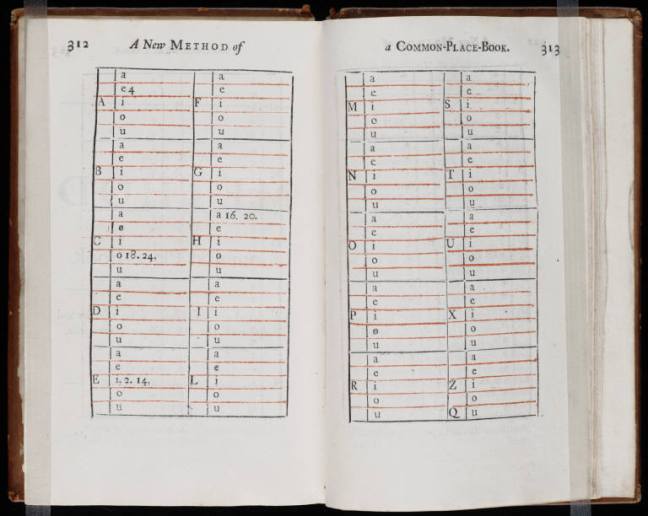

My standard stamina stunted, I offer only a collection of the most beautiful and striking encounters I had this week. To elevate the stature of what would otherwise just be a list (newsletters are indeed merely curation, indexing valuable only because the web is too vast), I’ll compare what follows to an early-modern commonplace book, the then popular practice of collecting quotations and sayings useful for future writing or speeches. True commonplaces, locus communis, were affiliated with general rules of thumb or tokens of wisdom; they played a philosophical role to illustrate the morals of stories in classical rhetoric. The likes of Francis Bacon and John Milton kept commonplace books. The most interesting contemporary manifestation of the practice is Maria Popova’s always delightful Brain Pickings. Popova, moreover, inspires the first selection in today’s list.

What delights me the most in compiling this list is that I can’t help but do so. There is much change afoot, and I wanted to grant myself the luxury of taking a weekend off. But I couldn’t. My mind will remain restless until I write. It’s a wonderful sign, these handcuffs of habit.

Without further ado, I present a collection of things that were meaningful to me this week:

Euclid alone has looked on beauty bare

Monday evening, my dear friend Alfred Lee and I walked 45 minutes to Pioneerworks in Red Hook to attend The Universe in Verse. It was packed: the line curved around the corner and slithered down Van Brunt street towards the water and, lemmings, we rushed to get two slices of pizza to stave off our hunger before the show. It was a momentous gathering, so touching to see over 800 people gathered to listen to people read poetry about science! Maria Popova introduced each reader and spoke like she writes, eloquence unparalleled and harkening the encyclopedic knowledge of former days. It was a celebration of feminism, of the will to knowledge against the shackles of tyranny, of minds inquisitive, uniting in the observation of nature always ineffable yet craftily crystallized under the constraints of form.

My favorite poems were those by Adrienne Rich and this sonnet by the very beautiful Edna St. Vincent Millay.

Euclid alone has looked on Beauty bare.

Let all who prate of Beauty hold their peace,

And lay them prone upon the earth and cease

To ponder on themselves, the while they stare

At nothing, intricately drawn nowhere

In shapes of shifting lineage; let geese

Gabble and hiss, but heroes seek release

From dusty bondage into luminous air.

O blinding hour, O holy, terrible day,

When first the shaft into his vision shone

Of light anatomized! Euclid alone

Has looked on Beauty bare. Fortunate they

Who, though once only and then but far away,

Have heard her massive sandal set on stone.

A glutton for abstraction and the traps of immutability and stasis, I found this poem gripping. I cannot help but imagine a sandal etched in white marble at the end, the toes of Minerva immutable, inexorable, ineluctable in the hallways of the Louvre, the memories of a younger self thirsting to understand our world. The nostalgia ever present and awaiting. Euclid declaring with such force that for him, σημεῖον sēmeion, a sign or mark, meant a point, that which has no parts. And from this point he built a world of beauty bare.

Nutshell

I’m reading McEwan’s latest, Nutshell. It’s marvelous. A contemporary retelling of Hamlet, where the doubting antihero is an unborn baby observing Gertrude and Claudius’s (Trudy and Claude, in the retelling) murderous plot from his mother’s womb.

There are breathtaking moments:

“But here’s life’s most limiting truth-it’s always now, always here, never then and there.”

“There was a poem you recited then, too good for one of yours, I think you’d be the first to concede. Short, dense, better to the point of resignation, difficult to understand. The sort that hits you, hurts you, before you’ve followed exactly what was said…The person the poem addressed I think of as the world I’m about to meet. Already, I love it too hard. I don’t know what it will make of me, whether it will care of even notice me…Only the brave would send their imaginations inside the final moments.”

I have a post arguing against immortality brewing, to respond to Konrad Pabianczyk and continue the relentless fight against the Silicon Valley Futurists. It’s not possible to love the world too hard if you never die. There’s something right about the Freudian death drive, the lyricism of the brink of decay. Gracq harnesses it to create the ecstatic psychology of Au Chateau d’Argol. Borges describes how the nature of choice, the value we ascribe the experiences-the beauty of coincidence, the feeling of wonder that two minds might somehow connect so deeply that, as the angel made man in Wenders’s Wings of Desire, the voices finally stop, where the loneliness halts temporarily to usher aloneness in peace, true aloneness in the company of another, another like you, with you deeply and fully-would disappear if we know that the probability of experiencing everything and the possibility of doing everything would go up if we could indeed live forever in this continual eternal return. And even way back when in Mesopotamia, in the days of the great Gilgamesh, the gods do grant Utnapishtim immortality, but on the condition of a life of loneliness, a life lived “in the distance, at the mouth of the rivers.”

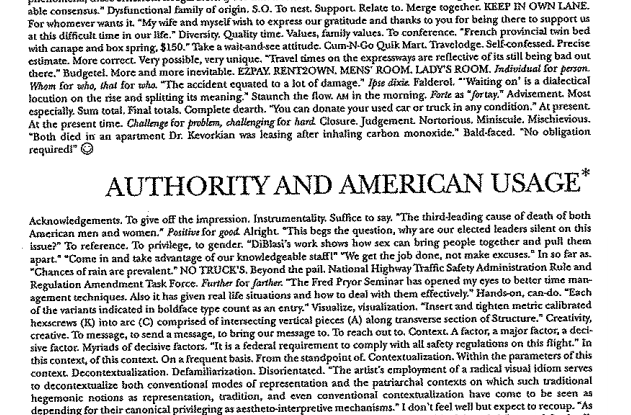

Style is an exercise in applied psychology

On Thursday morning, I listened to Steven Pinker (coincidentally, or perhaps not so coincidentally, in dialogue with Ian McEwan, McEwan with his deep voice, the English accent a paradigm of steadied wisdom worth attending to) talk about good writing on an Intelligence Squared podcast recorded in 2014. He basically described how bad writing, in particular bad academic writing, results from psychological maladies of having to preemptively qualify and defend every statement you make against the pillories of peers and critiques. His talk reminded me of David Foster Wallace’s essay Authority and American Usage, what with collapsing the distinction between descriptivist and prescriptivist linguistics and exposing the unseemly truth that style, diction, and language index social class. The gem I took away was Pinker’s claim that style is an exercise in applied psychology, that we must consider who our readers are, what they’ve read, how the speak and think, and adapt what we present to meet them there without friction or rejection.

What’s freeing about this blog is that, unlike most of my other writing, I forget about the audience. There is no applied psychology. It’s just a mind revealed and revealing.

Music

Coda by Aaron Martin/Christoph Berg caught my attention yesterday evening as I walked under the bridge from the Lorimer station and waited, reading, in front of a bar in Williamsburg.

I had this Proustian madeleine experience last Sunday when The Beatitudes, by Vladimir Martynov, showed up on my Spotify Discover Weekly list. The Kronos Quartet version is featured in Paolo Sorrentino’s The Great Beauty. Hearing the music transported me back to a wintry Sunday morning in Chicago, up at the Music Box theater to see that film with the man I lived with and loved at the time. I relived this love, deeply. It was so touching, and yet another type of experience I just don’t think would be as powerful and impactful if I weren’t mortal, if there weren’t this knowledge that it’s no longer, but somehow always is, a commonplace as old as Greece, tucked away like shy toes under the sandal strap of Minerva’s marble shoe, cold, material, inside me, deeply, until I die, to be unlocked and unearthed by surprise, as if it were again present.

The image is of John Locke’s 1705 “New method of a commonplace book.” Looks like Locke wanted to add some structure to the Renaissance mess of just jotting things down to ease future retrieval. This is housed in the Beinecke rare book library at Yale.