For without culture or holiness, which are always the gift of a very few, a man may renounce wealth or any other external thing, but he cannot renounce hatred, envy, jealousy, revenge. Culture is the sanctity of the intellect. William Butler Yeats, 1909

Culture is one of those slippery words everyone talks about but no one talks about in the same way. The etymology stems from the Middle French culture, meaning “the tilling of land,” itself from the Latin cultura (which shares roots with colony). It wasn’t until 1867 that culture was regularly used to describe the collective customs and achievements of a people. I haven’t confirmed this, but suspect this figurative use of the word occurred so late in history because what we currently call culture used to be called mores, the habits and customs that define the ethical norms of a community. Note that culture connotes activity, cultivation, education, the conscious act of shaping one’s activity to embody a certain set of values; mores connotes manners, customs, habit, the subconscious adoption of patterns set and reflected by others and ancestors. It’s possible-but again requires further research-that culture became the word used to describe the how of human activity in tandem with the rise of the autonomous, capitalist individual.

In the workplace, culture often gets reduced to the fluffy stuff of the HR department. At its most vapid, culture is having a cool office full of razor scooters, organic smoothies, and, as Dan Lyons mordantly and hilariously describes in the prologue to Disrupted, an aesthetic that “bears a striking resemblance to [a Montessori preschool]: lots of bright basic colors, plenty of toys, and a nap room with a hammock and soothing palm tree murals on the wall. The office as playground trend that started at Google and has spread like an infection across the tech industry.” Work as lifestyle, where every sip of Blue Bottle coffee signals our coolness, where every twist of wax on our mustaches imbues our days with mindful meaning as we hack our brains and the establishment (ignoring, for the time being, the premium we pay for those medium roast beans). At its most sinister, culture is overlooking implicit and even explicit acts of harassment, abuse, or misogyny to exclusively favor the ruthless promotion of growth (see Uber’s recent demise). At its most awkward, culture is the set of trust- and bond-building exercises conducted during the offsite retreat, where we do cartwheels and jumping jacks and sing Kumbaya holding hands in a circle once a year only to return to the doldrums at our dark mahogany corner offices and linoleum cubicles on Monday morning. At its most sinuous, culture is the set of minute power plays that govern decisions in a seemingly flat organization, the little peaks of hierarchy that arise no matter how hard we try to proclaim equality, the acrid taste we get after meetings when it’s obvious to everyone, although no one admits it, that deep down our values aren’t really aligned, and that master-slave dialectics always have and always will shape the course of history.

But culture can be much more than craft beer at hack night and costumes on Halloween. The best businesses take culture so seriously that it shifts from being an epiphenomenon to weaving the fabric of operations. The moment of transubstantiation takes place when a mission statement changes from being a branding tool to being a principle for making decisions; when leadership abandons micromanagement to guide employees with a north star, enabling ownership, autonomy, and creativity; when the little voices of doubt and fear and worry and concern inside our heads are quieted by purpose and clarity, when we feel safe to express disagreement without suffering and repercussion; when a whole far greater than the sum of its parts emerges from the unique and mystically aligned activities of each individual contributor.

This post surveys five companies for which culture is an integral part of operations. Each is inspiring in its own way, and each thinks about and pragmatically employs culture differently at a different phase of company history and growth.

Always Day 1: True Customer Obsession at Amazon

On April 12, Jeff Bezos released a letter to shareholders. Amazon is now 23 years old, and has gone from being an online bookstore to being the cloud infrastructure making many startups possible, the creator of the first convenience store without checkout lines, and one of the largest retailers in the world. Given its maturity and the immense scope of its operations, Amazon risks falling into big company traps, succumbing to the inertia of process and the albatross weight of the innovator’s dilemma. Such “Day 2” stupor is precisely what CEO Jeff Bezos wants to avoid, and his letter presents four cultural pillars to keeping a big company running like a small company: customer obsession, a skeptical view of proxies, the eager adoption of external trends, and high-velocity decision making.

Bezos states “true customer obsession” as the fulcrum guiding Amazon’s business. While this may seem like a given, in practice very few companies succeed at running a customer-centric business. As Bezos points out, businesses can be product focused, technology focused, or business model focused. They can be sales focused or lifestyle focused. They can focus on long-term strategy or short-term revenue. The popularity and design thinking stems from the fact that product development methodologies historically struggled to take into account how users reacted to products. In Creative Confidence, Tom Kelley and David Kelley show multiple examples of how feature prioritization decisions change when engineers leave the clean world of verisimilitude to enter the messy, surprising world of human reactions and emotions. One of my favorite examples in the Kelleys’ book is when Doug Dietz, an engineer at GE Healthcare, overhauled his strategy for building MRIs when he realized the best technical solution created a horrifying experience for children. The guiding architecture for MRIs henceforth became pirate ships or space ships, contextual vessels that could channel the imagination to dampen the aggressive clanging of the machine, and create a more positive experience for sick children.

Bezos astutely remarks that a customer-centric approach forces a company to stay innovative and uphold the hunger of Day 1 because “customers are always beautifully, wonderfully dissatisfied, even when they report being happy and business is great.” This is Marketing with a big M. Not marketing as many people misunderstand it, i.e., as the use of catch phrases or content to shape the opinions of some group of people in the hope that these shaped opinions can transform into revenue, but marketing as a sub-discipline of empiricism, where a company carefully observes the current habits of some group of people to discern a need they don’t yet have, but that they will willingly and easily recognize as a need, and change their habits to accommodate, once it’s presented as a possibility. Steve Jobs did this masterfully.

Using customers as an anchor to design and build new products is powerful because truth is stranger than fiction. Many product managers and engineers fall into the trap of verisimilitude, making products as they would write a play, where each detail seems to make sense in the context of the coherent whole. I’ve seen numerous companies spend months imagining features they think users will want that arise logically from the technical capabilities of a tool, only to realize meager revenues because users actually want something different. User stories built on real research with real people-even if it’s a sample set of a few rather than the many that support A/B testing methodologies at consumer companies like Netflix-have Sherlock Holmes superpowers, leading to insights that aren’t obvious until reinterpreted retrospectively.

Bezos ends his letter with the importance of high-velocity decision making, which involves the courage to make decisions with 70% of the information you wish you had and “disagreeing and committing” when consensus is impossible. Disagreeing and committing requires radical candor and the courage to embrace conflict head on. Early in my career, I failed on a few occasions by not having the courage to voice disagreement as we made certain important decisions; after the fact, when we started to observe the negative impacts of the decision, I wanted to stand up and say “I told you so!” but couldn’t because it was too late. This breeds resentment, and it certainly takes culture work to make employees feel like they can voice conflicting or dissenting views without negative repercussion.

(A couple of my readers pointed out that Amazon has been reported to have a cutthroat culture. This reminds me of Ferdinand Céline and Martin Heidegger, two men who supported Fascism and Nazism, and yet left us quite valuable writings. Should we pay attention to the idealized version of a man or company, the traces left in letters and prose, or the reality of his lived life and actions? Can we forgive the sinner if he leaves us gold?)

Soul as a Recruiting Tool at Integrate.ai

While Amazon is a massive company whose cultural challenge is to avoid inertia and bureaucracy, Integrate.ai is a brand-new startup whose challenge is to attract the right early talent that will make or break company success. Inspired by his experience at Facebook, CEO & Founder Steve Irvine decided the surest way to recruit top talent-and avoid hires whose values were misaligned-was to make it a priority to build a company with soul.

In a recent presentation, Irvine explains how soul is the hard-to-explain, intangible aspect of a business people struggle to pin down in words, one of those things you know when you see it but can’t really articulate or describe. He says it’s “what you do when no one is looking and when everyone is looking, what gives people in your company purpose and makes them brave in the face of long odds.” Underlying soul is a set of common values: Irvine believes its crucial that everyone in a company share values and mission, even if they approach different questions with a plurality and diversity of perspectives. Soul, here, is different from the spiritual essence of an individual, the self that remains after our corporeal bodies return to dust. It’s the least common denominator uniting a group of diverse individuals, the fulcrum that keeps everyone engaged when things aren’t going well, the life force sustaining interest and passion in the midst of doubt and dismay.

Perhaps most interesting is how effective commitment to soul can be. Irvine is at the very beginning of building his company, so soul, for the moment, is an abstract promise rather than an embodied commitment. But it’s extremely powerful to love what you do. To embrace work with passion, not just as a job that pays the bills. To be excited about weathering storms together with a group of people you care about and in the service of a mission you care for. The trick is to transform this energy into the hard work of building a business.

IKEA: The Best Company Mission Statement Ever

If there’s anyone who has managed to transform soul into successful operations, it’s IKEA founder Ingvar Kamprad. The Testament of a Furniture Dealer, which he wrote in 1976, is the most powerful company mission statement I’ve ever read. It’s powerful because it shows how the entirety of IKEA’s operations result, as if by logical necessity, from the company’s core mission “to create a better everyday life for the many people.”

Just after stating this core mission, Kamprad continues that they will achieve this mission “by offering a wide range of well-designed, functional home furnishing products at prices so low that as many people as possible will be able to afford them.” These two initial phrases function like axioms in a mathematical proof, with subsequent chapter in the Testament exploring propositions that logically follow from the initial axioms.

The first proposition regards what Kamprad calls product range, the set of products IKEA will and won’t offer. As the many people need to furnish not just their living rooms but their entire homes, IKEA’s objective must, as a result, “encompass the total home environment, [including] tools, utensils and ornaments for the home as well as more or less advanced components for do-it-yourself furnishing and interior decoration.” The product design must be “typically IKEA,” reflecting the company’s way of thinking and “being as simple and straightforward as ourselves.” The quality must be high, as the many people cannot afford to just throw things away.

To keep costs low, of course, requires “getting good results with small or limited resources.” Which, by logical necessity, leads to subsequent propositions about the cost of capital and inventory management. Kamprad says that “expensive solutions to any kind of problem are usually the work of mediocrity.” Rigorous pragmatism, and having a sense for the entire supply chain of costs to create and distribute a product, is a core part of IKEA’s culture. Considering waste of resources to be “one of the greatest diseases of mankind,” Kamprad builds the cultural mindset that leads to the compact, do-it-yourself assembly packaging for which IKEA is famous.

And the brilliance continues. Kamprad pivots from simplicity in design and production to simplicity as a virtue in decision making, claiming, like Bezos, that “exaggerated planning is the most common cause of corporate death” and extolling a rigorous curiosity that always asks why things are done a given way to open the critical curiosity required to identify opportunities to do things differently. He extols concentration, the discipline required to focus on the specific range of products that defines core identity, the type of focus Steve Jobs instilled to usher Apple to its current level of success. And finally, Kamprad closes his mission by celebrating incompletion and process:

“The feeling of having finished something is an effective sleeping pill. A person who retires feeling that he has done his bit will quickly wither away. A company which feels it has reached its goal will quickly stagnate and lose its vitality.

Happiness is not reaching your goal. Happiness is being on the way. It is our wonderful fate to be just at the beginning. In all areas. We will move ahead only by constantly asking ourselves how what we are doing today can be done better tomorrow. The positive joy of discovery must be our inspiration in the future too.

The word impossible has been deleted from our dictionary and must remain so.”

Note that he wrote this in 1976, a good 35 years before the current new-age thinking focusing on the joy of the process was commonplace wisdom. Note the parallels with Bezos, how both leaders focus on creativity, discipline, and the ruthless awareness and avoidance of biases as a means to keep innovation alive. IKEA has grown from being a low-cost furniture provider in Europe to being a global franchise business with operations in many markets. Time will tell what it will mean for them to serve the many people in the future, and how they will expand their product range while adhering to the focus and discipline required to keep their identity and mission intact.

Commitment to Diversity at Fast Forward Labs

On February 23, 2017, Hilary Mason, the founder and CEO of Fast Forward Labs, sent the following email to our team:

Subject: Maintaining a Respectful Environment

Body:

It’s very important to me that our office is respectful and comfortable for everyone who works here and for our visitors, many of whom we are trying to engage as customers and collaborators.

To that end: PUT THE TOILET SEAT DOWN.

There is writing on the seat to remind you.

Thank you,

Culture as Product at Asana

The final example focuses on practices to make culture a critical component of a business as opposed to an office decoration or afterthought at the company party. Asana, which offers a SaaS project-management tool, has received multiple accolades for its positive culture, including a rare near-perfect rating on Glassdoor. Short of using Putin-style coercion and manipulation techniques, how did they achieve such positive employee ratings on culture and experience?

According to a recent Fast Company article, by “treating culture as a product that needed to be carefully designed, tested, debugged, and iterated on, like any other product they released.” Just as Amazon analyzes feedback from their external market, so too does Asana analyze feedback from their internal market, soliciting feedback from employees and “debugging” issues like false empowerment as soon as they arise. The company also offers the standard cool office perks that are commonplace in the valley, offering each employee $10,000 (!!!) to set up customized workplaces that can include anything from standing desks to treadmills.

It’s likely risky to adopt Asana’s culture as product model given the gimmick of hacking phenomena-like our minds and cultural practices-that aren’t computer code. But the essence here is to manage culture using the tools you know well. Agile software development practices aren’t universal across all companies, so it would be a stretch to apply them in environments where they’re not a great fit. But if we take this to a more abstract and general level, it does make sense to treat culture as a living, moving, dynamic product that requires work and discipline just like the products a business offers to its customers, and to manage it accordingly.

Conclusion

The older I get, the more I’m convinced that the how of activity is more important to happiness than the what of activity. Culture is the big how of a company that emerges from the little hows of each individual’s daily activities. When norms were mores, the how was inherited and given, habits and manners we had to adopt to align civil interaction. Now that norms are culture, we’re empowered to create our how, to have it trickle down from mission into operations or work actively to build it and debug it like a product. This requires vigilance, mindfulness, responsibility. It requires humbleness and, as Ingvar Kamprad concludes, “the ambition to develop ourselves as human beings and co-workers.”

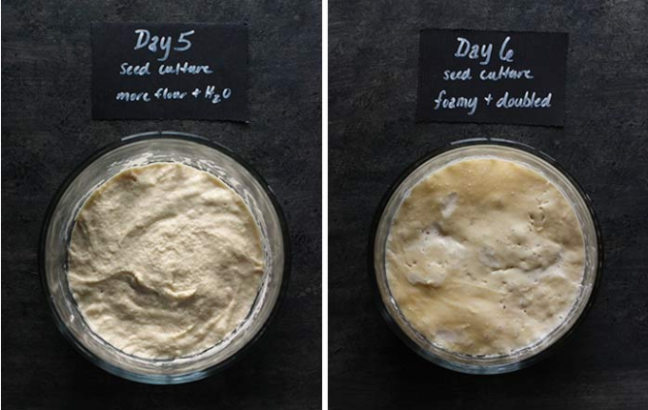

The image is from Soup Addict’s recipe for a wild yeast sourdough starter. It’s valuable for us to remember the agricultural roots of the world culture, to bring things back to earth and remember the hard work required to care for something larger than and different from ourselves, which, once it reaches maturity, can feed and nourish us.