Touch is the most basic, the most non-conceptual form of communication that we have. In touch there are no language barriers; anything that can walk, fly, creep, crawl, or swim already speaks it. - Ina May Gaskin, Spiritual Midwifery

Sometimes we come into knowledge through curiosity. Sometimes through imposed convention, as with skills learned during a course of study. Other times knowledge comes into us through experience. We don’t seek. The experience happens to us, puzzling us, challenging our assumptions, inciting us to think about subject we wouldn’t have otherwise thought much about. That this knowledge comes upon us without our seeking enforces a sense that it must be important. Often it lies dormant, waiting to come to life. [1]

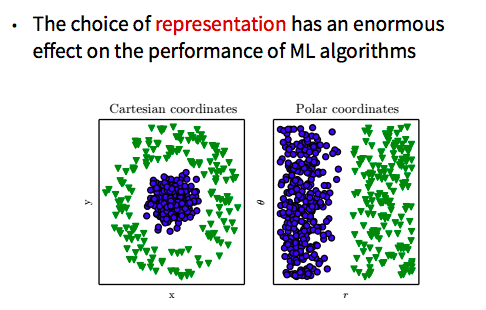

I have never thought deeply about how and what we communicate through touch. I’ve certainly felt the grounding power of certain yoga teachers’ hands as they rubbed my temples and forehead during savasana. I’ve been attuned to how the pressure of a hug from a girlfriend in high school signaled genuine affection or a distancing disgust, the falseness of their gesture signaled through limp hands just barely grazing a fall jacket. When placing my hand on the shoulder of someone who reports to me at work, preparing to share positive feedback on a particular behavior, I’ve consciously modulated the pressure of my hand from gentle to firm, both so as not to startle them away from their computer and to reinforce the instance of feedback. Most of my thinking about communication, however, has hovered in the realm of representation and epistemology, trapped within the tradition that Richard Rorty calls the Mirror of Nature, where we work to train the mind to make accurate representations of the external world. Spending the last five years working in machine learning has largely reinforced this stance: I was curious to understand how learned mathematical models correlated features in images with output labels that name things, curious to understand the meaning-making methods of machines, and what these meaning-making methods might reveal about our own language and communication.

And then I got pregnant. And my son Felix grew inside me, continues to grow inside me, inching closer to his birth day (38 weeks and counting). And while, like many contemporary mothers-to-be, I initially watched to see if he responded differently to different kinds of music, moving more to the Bach Italian Concerto or a song by Churches or Grimes, while I was initially interested in how he would learn the unique intonations of his mother and father’s voice, my experience of interacting with Felix changed my focus from sound to touch. My unborn son and I communicate with our hands and feet. The surest way to inspire him to move is to rub my abdomen. The only way he can tell me to change a position he doesn’t like is to punch me as hard as he can. Expecting mothers rub their bellies for a reason: it’s an instinctual means of communicating, transforming one’s own body into the baby’s back, practicing the gentle, circular motions that will calm the baby outside the womb. Somehow it took the medical field until 2015 to conduct a study concluding that babies respond more to a mother’s touch than her voice. I can’t help but see this is the blindspot of a culture that considers touch a second-class sense, valued lower than the ocular or even auricular.

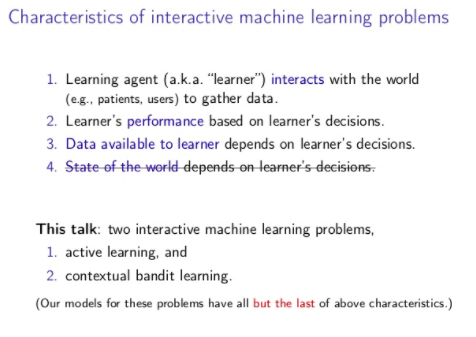

But as research in artificial intelligence and robotics progresses, touch may reclaim a higher rank in the hierarchy of the senses. Brute force deep learning (brute force meaning throwing tons of data at an algorithm and training using gradient descent) has made great strides on vision, language, and time series prediction tasks over the past ten years, threatening established professional hierarchies that compensate work like accounting, law, or banking higher than professions like nursing or teaching (as bedside manner and emotional intelligence is way more complex than repetitive calculation). We still, however, have work to do to make robots that gracefully move through the physical world, let alone do something that seems as easy as pouring milk into our morning cereal or tying our shoes. Haptics (the subfield of technology focused on creating touch using motion, vibration, or force) researcher Katherine Kuchenbecker puts it well in Adam Gopnik’s 2016 New Yorker article about touch:

Haptic intelligence is vital to human intelligence…we’re just so smart with it that we don’t know it yet. It’s actually much harder to make a chess piece move correctly-to pick up the piece and move it across the board and put it down properly-than it is to make the right chess move…Machines are good at finding the next move, but moving in the world still baffles them.

And there’s more intelligence to touch than just picking things up and moving them in space. Touch encodes social meaning and hierarchy. It can communicate emotions like desire and love when words aren’t enough to express feelings. It can heal and hurt. Perhaps it’s so hard to describe and model haptic intelligence because it develops so early that it’s hard for us to get underneath it and describe it, hard to recover the process of discovery. Let’s try.

Touch: Space, Time, and the Relational Self

Touch is the only sense that is reflexive.[2] Sure, we can see our hands as we type and smell our armpits and taste the salt in our sweat and hear how strange our voice sounds on a recording, but there’s a distance between the body part doing the sensing and the body part/fluid being sensed. Only with touch can we place the pad of our right pointer finger on the pad of our left pointer finger and wonder which finger is touching (active) and which finger is being touched (passive). The same goes if we touch our forearm or belly button or the right quadricep just above the knee, we’re just so habituated to our hands being the tool that touches that we assume the finger is active and the other body part is passive.

In his 1754 Traité des sensations[3], the French Enlightenment philosopher Étienne Bonnot de Condillac went so far as to claim that the reflexivity of touch is the foundation of the self. Condillac was still hampered by the remnants of a Cartesian metaphysics that considered there to be two separate substances: physical material (including our bodies) and mental material (minds and souls). But he was also steeped in the Enlightenment Empiricism tradition that wanted to ground knowledge about the world through the senses (toppling the inheritance of a priori truths we are born with). The combination of his substance dualism (mind versus body) and sensory empiricism results in a fascinating passage in the Traité where a statue, lacking all senses except touch, comes to discover that different parts of her body belong to the same contiguous self. The crux of Condillac’s challenge starts with his remark that corporeal sensations can be so intertwined with our sense of self that they are more like “manners of being of the soul” than sensations localized in a particular body part. The statue needs more to recognize the elision between her corporeal and mental self. So Condillac goes on to say that solid objects cannot occupy the same space: “impenetrability is a property of all bodies; many cannot occupy the same space; each excludes the others from the space it occupies.” When two parts of the body come in contact with one another, they hit resistance because they cannot occupy the same spot. The statue would therefore notice that the finger and the belly are two, different, mutually exclusive parts of space. At the same time, however, she’d sense that she was present in both the finger and the belly. For Condillac, it’s this the combination of difference and sameness that constitutes the self-reflexive sense of self. And this sensation will only be reinforced when she then touches something outside herself and notices that it doesn’t touch back.

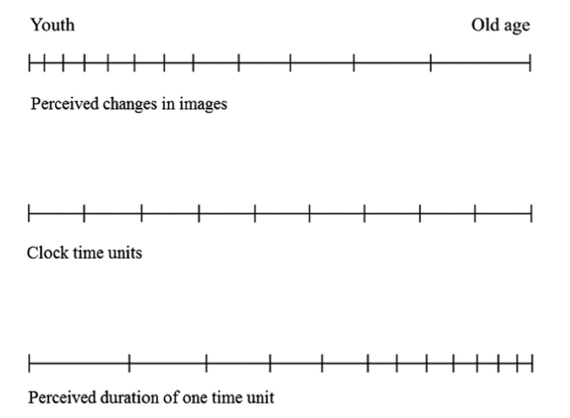

For Condillac touch unifies the self in space. But touch can also unify the self in time. When I struggled sleep as a child, my mother would stroke my hair to calm me down and help me find sleep. The movement of her hand from temple to crown had a particular speed and pressure that my brain encoded as palliative. When I receive a similar touch today, the response is deep, instant, so deep it transcends time and brings back the security I felt as a child. But not merely security: the transition from anxiety to security, where the abrupt change in state is even more powerful. Mihnea, father to the unborn child growing inside me, knew this touch before we met. I didn’t need to ask him, didn’t need to provide feedback on how he might improve it better to soothe me. It was in him, as if it were he who was present when I couldn’t sleep as child. And not in some sick Freudian way — I don’t love him because he harkens memories of my mother. It’s rather that, early in our relationship, I felt shocked into love for him because his touch was so familiar, as if he had been there with me throughout my life. The wormhole his hand opened wasn’t quite Proustian. It wasn’t a portal to bring back scenes form childhood that lay dormant, ready to be relived (or, as Proust specifies, created, rather than recovered). It was more like a black hole, collapsing my life into the density of Mihnea’s touch, telling me he would father our children and know how to help them sleep when they were anxious.

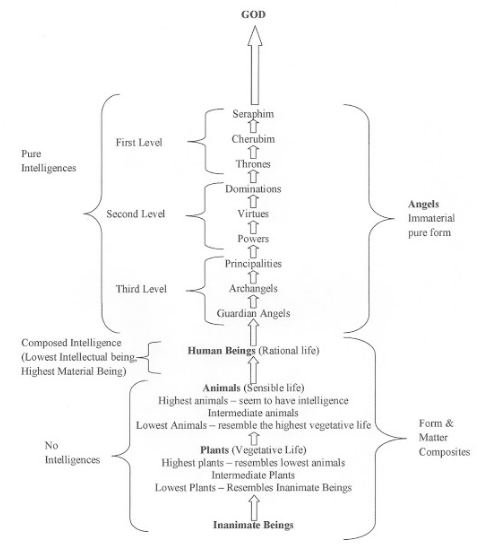

There’s an implicit assumption guiding the accounts of Condillac and Mihnea’s touch: that, to use Adam Gopnik’s words, “we are alive in relation to some imagined inner self, the homunculus in our heads.” But touch becomes even more interesting when it helps us understand “consciousness itself as ‘exteriorized’, [where] we are alive in relation to others…[where] our experience of our bodies-the things they feel, the moves they make, and the textures and people they touch-is our primary experience of our minds.” Here Gopnik describes the thinking of Greater Good Science Center founding director Dacher Keltner, who (I think, based upon the little I know…) disagrees the Kantian tradition that morality is grounded in reason and self-imposed laws and instead grounds morality in the touch that begins with the skin-to-skin contact between mother and child.

I think the magic here lies in how responsive touch can or even must be to be effective communication. Touch seems to be grounded on experimentation and feedback. We imagine what the person we are about to touch will sense when we place our hand upon their arm, perhaps even test the pressure and speed of our movements on our own forearms before trying it out on them. And then we respond, adapt, feel how their arms encounter our fingers and palms, watch how their eyes betray what any emotions our touch elicits in them, listen for barely audible sounds that indicate pleasure or security or contentment or desire or disgust. Touch seems to require more attention to the response of the other than verbal communication. We might (albeit often incorrectly) presume we’ve transmitted a message or communicated some thought to others when we say something to them. It’s better when we watch how they respond, whether they have captured what we mean to say, but so often we’re more focused on ourselves than the other to whom we seek to communicate. This solipsism doesn’t pass with touch. Our hands have to listen. And when they do, the effect can be electric. The one being touched feels attended to in a way that can go beyond verbal and cognitive understanding. Here’s how Ina May Gaskin described an encounter with a master of touch, a capuchin monkey:

She took hold of my finger in her hand-it was a slender, long-fingered hand, hairy on the back with a smooth black palm-and I had never been touched like that before. Her touch was incredibly alive and electric…I knew that my hand, and everyone else’s too, was potentially that powerful and sensitive, but that most people think so much and are so unconscious of their whole range of sensory perceptors and receptors that their touch feels blank compared to what it would feel like if their awareness was one hundred percent. I call this “original touch” because it’s something that everybody as a brand new baby, it’s part of the tool kit…Many of us lose our “original touch” as we interact with our fellow beings in fast or shallow manner.

Gaskin goes even further than Keltner in considering touch to be the foundation of morality. For her, touch is the midwife’s equivalent of the monk’s mind, and the midwife should take spiritual vows and abide by spiritual practices to “keep herself in a state of grace” required to tap into the holiness of birth. In either case, touch topples an interior, homunculus notion of self. The power lies in giving ourselves over to our senses, being attuned to others and their senses. Being as present as a capuchin monkey.

Haptics: Extending the Boundaries of the Self

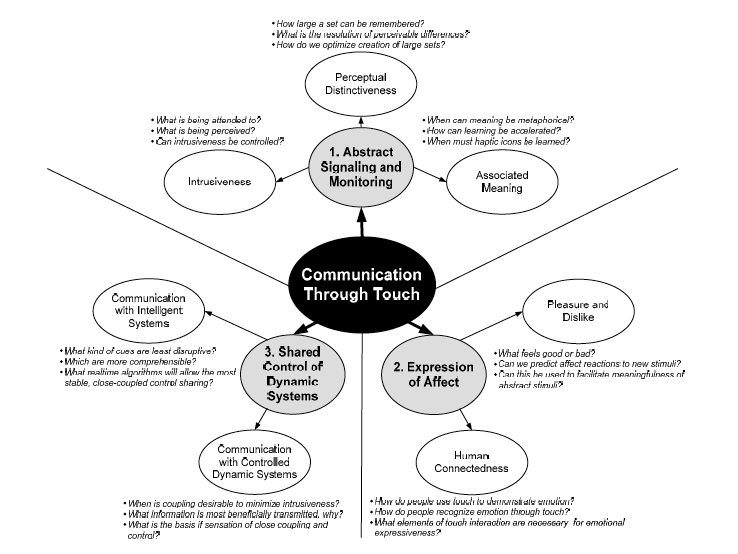

This focus on presence, of getting back to our mammalian roots, may strike some readers as parochial. We’re past that, have evolved into the age of digital communication, where, like the disembodied Samantha from Spike Jonze’s Her, we can entertain intellectual orgies with thousands of machine minds instantaneously, no longer burdened by the shackles of a self confined to a material body in space. The haptics research community considers our current communication predicament to be paradoxical, where the very systems designed to bring us closer together end up leaving us empty, fragmented, distracted, and in need of the naturalness of touch. So Karon Maclean (primary author), a prominent researcher in the field:

Today’s technology has created a paradox for human communication. Slicing through the barrier of physical distances, it brings us closer together-but at the same time, it insulates us from the real world to an extent that physicality has come to feel unnatural…Instant messaging, emails, cell phones, and shared remote environments help to establish a fast, always-on link among communities and between individuals…On the other hand, technology dilutes our connection with the tangible material world. Typing on a computer keyboard is not as natural as writing with a nice pen. Talking to a loved one over the phone does not replace a warm hug.

Grounding research in concrete case studies centered around the persona of a traveling sales woman named Tamara, Maclean and her co-authors go on to describe a few potential systems that can communicate emotions, states of being, and communicative intention through touch. One example uses a series of quickening vibrations on a mobile phone to mimic an anxious heart rate, signaling to Tamara that something is wrong with her son. Tamara can use this as an advanced warning to check her text messages and learn that her 5-year-old son is in the hospital after cutting himself on a rusty nail. In another example, Tamara sends a vibrating signal to a mansplaining colleague who won’t let her get a word in edgewise. The physical signals don’t require the same social awkwardness that would be required to cut off a colleague with a speech act, but end up leading to more collaborative professional communication.

Maclean is but one researcher among many working on creating sensations of touch at a distance. My personal favorite is long-distance Swedish massage to feel more closely connected with a partner. Students in Katherine Kuchenbecker’s research lab at the Max Planck Institute have published many papers over the last couple of years focusing on generating a remote sense of touch for robot-assisted surgery, to make the process feel more present and real for a human surgeon operating at a distance. Other areas of focus for haptics research are on prosthetics. Gopnik’s article is a good place for layman interested in the topic to start. I found the most interesting conclusions from the work to be how sensory input needs to be manipulated to be cognizable as touch. Raw input may just come off as a tingle, a simulated nerve sensation in an artificial limb; it needs modification to become a sensation of pressure or texture. All in all, the field has advanced a long way from the vibrations gaming companies put into hand-held controllers to simulate the experience of an explosion, but it still has a long way to go.

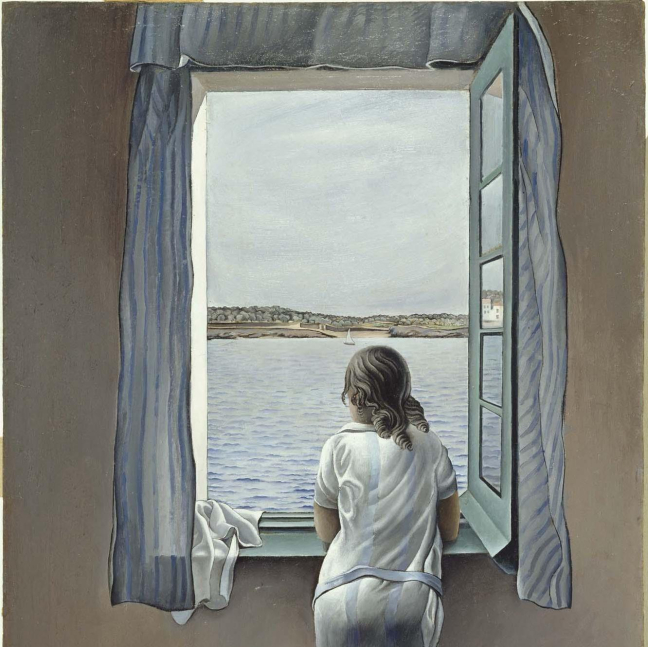

Let’s imagine that, sometime soon, we will have a natural, deep sense of touch at a distance, with the same ease that today we can send slack messages to colleagues working across the globe. Would we feel ubiquitous? Would our consciousness extend beyond the limitations of our physical bodies in a way deeper and more profound that what’s available with the visual and auditory features that govern our digital experience today? Will we be able to recover our “original touch” at a distance, knowing the Jerónimos Monastery in Lisbon more intimately because we can feel the harsh surface of its Lioz pillars, can sense, through the roughness of its texture, the electric remnants of the fossils that gird its core?

I just don’t think anything can replace the sanctity of our presence. The warmth and smell and stickiness of a newborn baby on our skin. The improbable wonder of a body working to defy entropy, if only for the short while of an average human lifespan. This doesn’t mean that the tapping into the technology of touch isn’t worthwhile. But it does mean that we can’t do so at the expense of losing the holiness of a different means of extending beyond the self through the immediate connections to another. At the expense of not learning from the steady rhythm of kicks and squirms that live within me, and will soon come to join us in our breathing world.

[1] What I’m trying to get at is different from the sociological concept of Verstehen, a kind of deep understanding that emerges from first-person experience. There’s definitely a part of this kind of knowledge that is grounded in having the experience, versus understanding something theoretically or at a distance. But the key is that the discovery of the insight wouldn’t have come to pass without the experience. I am writing this post - I have become so interested in touch - because of the surprising things I’ve come to learn during pregnancy. Without the pregnancy, I’m not sure I would have been interested in this topic.

[2] I think this is accurate, but would welcome if someone showed the contrary.

[3] This is one of my favorite texts in the history of philosophy. I also referenced it in Three Takes on Consciousness.

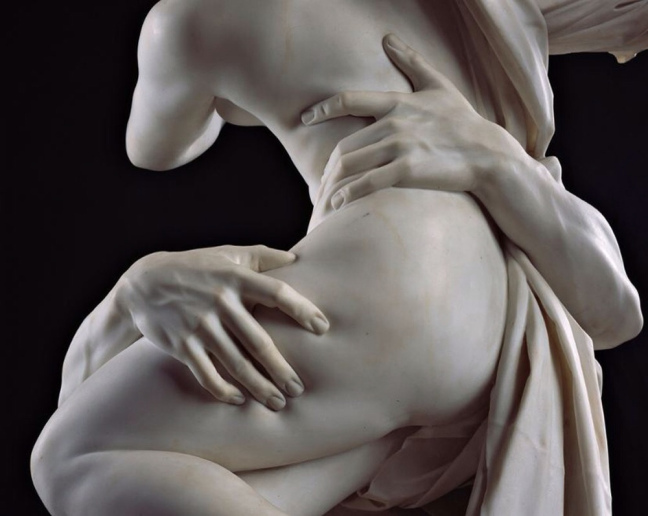

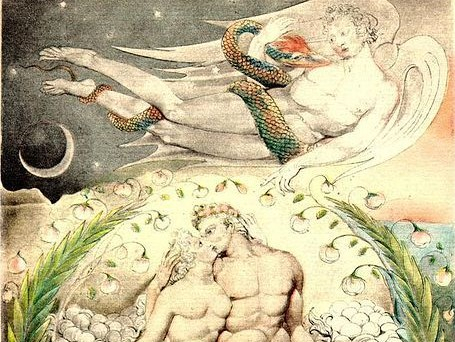

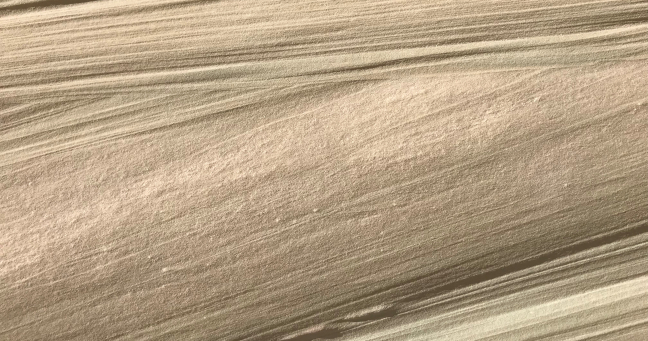

The featured image is a detail from Bernini’s Rape of Proserpina, housed in the Galleria Borghese in Rome. Bernini was only 23 years old when he completed the work. Proserpina, also known as Persephone, was the daughter of Demeter, the goddess of harvest and agriculture. Hades loved Proserpina, and Zeus permitted him to abduct her down to the underworld. Demeter was so saddened by the disappearance of her daughter that she neglected to care for the land, leading to people’s starvation. Zeus later responds to the hungering people’s pleas by making a new deal with Hades to release Proserpina back to the normal world; before doing so, however, Hades tricks her into eating pomegranates. Having tasted the fruit of the underworld, she is doomed to return there each year, signaling the winter months when the harvest goes limp. The expressiveness of Hades’ fingers digging into Proserpina’s thigh illustrates the complexity of touch: her resistance and fear shout from creases of marble muscles, fat, and skin. And somehow Bernini’s own touch managed to foster the emotionality of myth in marble, to etch it there, capturing the fleeting violence of rape and abduction for eternity.