Most writing defending the value of the humanities in a world increasingly dominated by STEM focuses on what humanists (should) know. If Mark Zuckerberg had read Mill and De Tocqueville, suggests John Naughton, he would have foreseen political misuse of his social media platform. If machine learning scientists were familiar with human rights law, we wouldn’t be so mired in confusion on how to conceptualize the bias and privacy pitfalls that sully statistical models. If greedy CEOs had read Dickens, they would cultivate empathy, the skill we all need to “put ourselves in someone else’s shoes and see the world through the eyes of those who are different from us.”

I agree with Paul Musgrave that “arguments that the humanities will save STEM from itself are untenably thin.” Reading Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics won’t actually make anyone ethical. Reading literature may cultivate empathy, but not nearly enough to face complex workplace emotions and politics without struggle. And given how expensive a university education has become, it’s hard to make the case of art for art’s sake when only the extremely elite have the luxury not to build marketable skills.

But what if training in the humanities actually does build skills valuable for a STEM economy? What if we’ve been making the wrong arguments, working too hard to make the case for what humanists know and not hard enough to make the case for how humanists think and behave? Perhaps the questions could be: what habits of mind do students cultivate in the humanities classroom and are those habits of mind valuable in the workplace?

I wrote about the value of the humanities in the STEM economy in early 2017. Since that time, I’ve advanced in my career from being an “individual contributor” (my first role was as a marketing content specialist for a legal software company) to leading teams responsible for getting things done. As my responsibilities have grown, I’ve come to appreciate how valuable the ways of speaking, writing, reading, and relating to others I learned during my humanities PhD are to the workplace. As a mentor Geoffrey Moore once put it, it’s the verbs that transfer, not the nouns. I don’t apply my knowledge of Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz at work. I do apply the various critical reading and epistemological skills I honed as a humanities student, which have helped me quickly grow into a leader who can weave the communication fabric required to enable teams to collaborate to do meaningful work.

This post describes a few of these practical skills, emphasizing how they were cultivated through deep work in the humanities and are therefore not easily replaced by analogue training in business administration or communication.

David Foster Wallace’s 2005 Kenyon College Commencement speech shows how powerful arguments in favor of a liberal arts education can be when they need not justify material payoff

Socratic Dialogue and Facilitating Team Discussion

Humanities courses are taught differently from math and science courses. Precisely because there is no one right answer, most humanities courses use the Socratic Method. The teacher poses questions to guide student dialogue around a specific topic, helping students question their assumptions and leave with a deeper understanding of a text than they did when they came to the seminar. It’s hard to do this well. Students get off topic or cite arguments or examples that aren’t common knowledge. Some hog the conversation and others are shy. Some teachers aren’t truly open to dialogue, and pretend the discuss when they’re really just leading students to accept their interpretation.

At Stanford, where I did my graduate degree, History professor Keith Baker stands out as the king of Socratic dialogue. Keith always reread required reading before class and opened discussion with one turgid question, dense with ways the discussion might unfold. Teaching D’Alembert and Diderot’s preface to the French Encyclopédie, for example, he started by asking us to explain the difference between an encyclopedia and a dictionary. The fact this feels like common sense is what made the question so poignant, and, for the French Enlightenment authors, the distinction between the two revealed much about the purpose of their massive work. The question forced us to step outside our contemporary assumptions and pay attention to what the same words meant in a different historical context. Whenever the discussion got off track, Keith gracefully posed a new question to bring things back on point without offending a student, fostering a space for intellectual safety while maintaining rigor.

The habits of mind and dialogue trained in a Socratic seminar are directly applicable to product management, which largely consists in facilitating structured discussions between team members who see a problem differently. In my work leading machine learning product teams, I frequently facilitate discussions with scientists, software developers, and business subject matter experts. Each thinks differently about what should be done and how long it will take. Researchers are driven by novelty and discovery, by developing an algorithm that pushes the boundary of what has been possible but which may not work given constraints from data and the randomness in statistical distributions. Engineers want to find the right solution to meet the constraints for a problem. They need clarity and don’t mind if things change, but need some stability so they can build. The business team represents the customer, focusing on success metrics and what will please or hook a user. The product manager sits between all these inputs and desires, and must take into account all the different points of view, making sure everyone is heard and respected, but getting the team to align on the next action.

Socratic methods are useful in this situation. People don’t want to be told what to do; they want to be part of a collective decision process where, as a team, they have each put forth and understood compromises and trade-offs, and collectively decided to go forward with a particular approach. A great product manager starts a discussion the same way Keith Baker would, by providing a structure to guide thinking and posing the critical question to help a group make a decision. The product manager pays attention to what everyone says, watches body language and emotional cues to capture team dynamics. She nudges the dialogue back on track when teams digress without alienating anyone and builds a moral of collective and autonomous decision making so the team and progress forward. She applies the habits of mind and dialogue practiced in the years in a humanities classroom.

Philology and Writing Emails for Many Audiences

My first year in graduate school, I took a course called Epic and Empire, which traced the development of the Western European epic literary tradition from Homer’s Iliad to Milton’s Paradise Lost. The first thing we analyzed when starting a new text was how the opening lines compared and contrasted to those we’d read before. Indeed, epics start with a trope called the invocation of the muse, where the poet, like a journalist writing a lede, informs the reader what the subject of the poem is about using a humble-boasting move that asks the gods to imbue him with knowledge and inspiration.

So Homer in the Iliad:

Sing, Goddess, sing the rage of Achilles, son of Peleus—

that murderous anger which condemned Achaeans

And Vergil signaling that the Aeneid is Rome’s answer to the Iliad, but that an author as talented as Vergil need not depend on the support from the gods:

Arms and the man I sing, who first made way,

predestined exile, from the Trojan shore

to Italy, the blest Lavinian strand.

And Ariosto, an Italian author, coyly signaling that it’s time women had their chance at being the heroines of epics (the Italian starts with Le Donne):

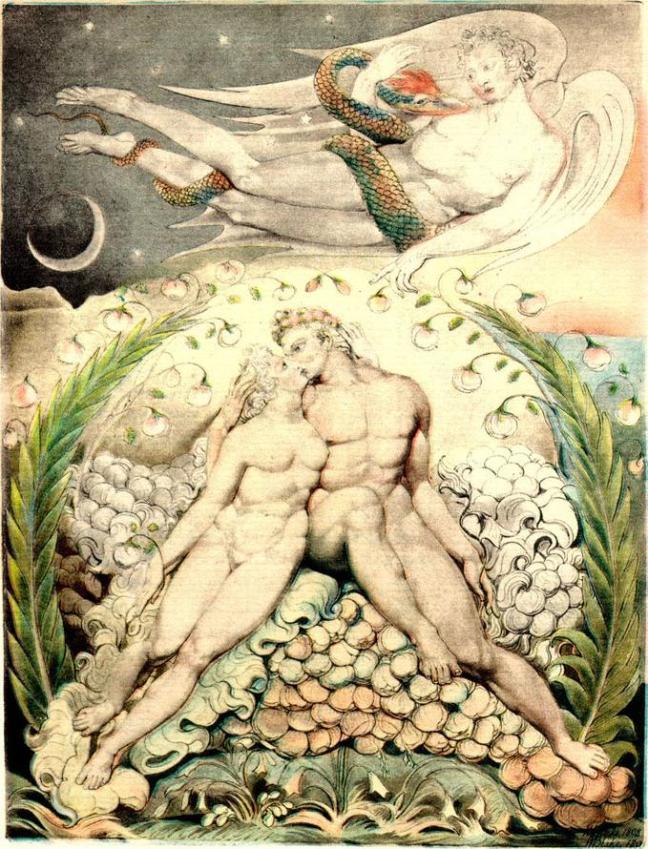

Studying literature this way, one learns not just knowledge of historical texts, but the techniques authors use to respond to others who came before them. Students learn how to tease out an extra layer of meaning above and beyond what’s written. The first layer of meaning in the first lines of Paradise Lost is simply what the words refer to: this is a story about Adam and Eve eating the forbidden fruit. But the philologist sees much more: Milton decides to hold the direct invocation to the muse until line six so he could foreground a succinct encapsulation of the being in time of all Christians, waiting from the time of the fall until the coming of Christ; does that mean he wanted to signal that first and foremost this is a Christian story, with the Greek tradition, signaled by the reference to Homer, only arriving 5 lines later?

Reading between the lines like this is valuable for executive communications, in particular in the age of email where something written for one audience is so easily forwarded to others without our intending or knowing. Business communications don’t just articulate propositions about states of affairs; they present facts and findings to persuade someone to do something (to commit resources to a project, to spend money on something, to hire or fire someone, to alter the way the work, or simply to recognize that everything is on track and no worry is required at this time). Every communication requires sensitivity to the reader’s presumed state of mind and knowledge, reconstructing what we think they know or could know to ensure the framing of the new communication lands. Each communication should build on the last communication, not using the stylistic invocation to the muse like Homer, but presenting what’s said next as a step in a narrative in time. And at one moment in time, different people in different roles interpret communications differently, based on their particular point of view, but more importantly their particular sensitivities, ambitions, and potential to be threatened or impacted by something you say. Executives have to think about this in advance, write things as if they were to be shared far beyond the intended recipient with his or her point of view and stakes in a situation. Philology training in classes like Epic and Empire is a good proxy for the multi-vocal aspects of written communications.

Making Sense of Another’s World: The Practice of Analytical Empathy

In 2013, I gave a talk about why my graduate work in intellectual history formed skills I would later need to become a great product marketer. As in this post, my argument in that talk focused not on what I knew about the past, but how I thought about the past: as an intellectual historian focused on René Descartes’ impact on 17th-century French culture, I sought to reconstruct what Descartes thought he was thinking, not whether Descartes’ arguments were right or wrong and should continue to be relevant today or relegated to the dustbin of history (as a philosopher would approach Descartes).

Doing this well entails that one get outside the inheritance of 400 years of interpretation that shape how we interpret something like Descartes’ famous Cogito, ergo sum, I think, therefore I am. Most philosophers get accustomed to seeing Descartes show up as a strawman for all sorts of arguments, and consider his substance dualism (i.e., that mind and body are totally separate kinds of matter) is junk in the wake of improved understanding about the still mysterious emergence of mind from matter. They solidify an impression of what they think he’s saying as seen from the perspective of the work philosophy and cognitive science seeks to do today. As an intellectual historian, I sought to suspend all temptation to read contemporary assumptions into Descartes, and to do what I could to reconstruct what he was thinking when he wrote the famous Cogito. I read about his upbringing as a Jesuit and read Ignatius of Loyola’s Spiritual Exercises to better understand the genre of early-modern meditations, I read the texts by Aristotle he was responding to, I read seminal math texts from the Greeks through the 16th-century Italians to understand the state of mathematics at the time he wrote the Géometrie, I read not only his Meditations, but also all the surrounding responses and correspondence to better understand the work he was trying to accomplish in his short and theatrical philosophical prose. And after doing all this work, I concluded that we’ve misunderstood Descartes, and that is famous Cogito isn’t a proposition about the prominence of mind over body, but rather a meditative mantra philosophers should use to train their minds to think “clear and distinct” thoughts, the axiomatic backbones for the method he wanted to propose to ground the new science. And Descartes was aware we are all to prey to fall into old habits, that we had to practice mantras every day to train the mind to take on new habits to complete a program of self-transformation. I didn’t care if he was right or wrong; I cared to persuade readers of my dissertation that this was the work Descartes thought the Cogito was doing.

A talk I gave in 2012 about why my training in intellectual history helped be become a good product marketer, a role that requires analytical empathy.

This skill, the skill of suspending one’s own assumptions about what others think, of not approaching another’s worldview to evaluate whether its right or wrong, but of working to make sense of how another lives and feels in the world, is critical for product management, product marketing, and sales. Product has migrated from being an analytical discipline focused on triaging what feature to build next to maximize market share to being an ethnographic discipline focused on what Christian Madsbjerg calls analytical empathy (Sensemaking), a “process of understanding supported by theory, frameworks, and an engagement with the humanities.” This kind of empathy isn’t just noticing that something might be off with another person and searching to feel what that other person likely feels. It’s the hard work of coming to see the world the way another sees it, patiently mapping the workflows and functional significance and emotions and daily habits of a person who encounters a product or service. When trying to decide what feature to build next in a software product, an excellent product manager doesn’t structure interviews with users by posing questions about the utility of different features. They focus on what the users do, seek to become them, just for one day, watch what they touch, what where they move cursors on screens, watch how the muscles around their eyes tighten when they get frustrated with a button that’s not working or when they receive a stern email from a superior. They work to suspend their assumptions about what they assume the user wants or needs and to be open to experiencing a whole different point of view. Similarly, an excellent sales person comes to know what makes their buyers tick, what personal ambitions they have above and beyond their professional duties. They build business cases that reconstruct the buyers’ world and convincingly show how that world would differ after the introduction of the sellers’ product or service. They don’t showcase bells and whistles; they explain the functional significance of bells and whistles within the world of the buyer. They make it make sense through analytical empathy.

Business school, in particular as curriculum exists today, isn’t the place to practice analytical empathy. And humanities courses that are diluted to hone supposedly transferrable skills aren’t either. The humanities, practiced with rigor and fueled by the native curiosity of a student seeking deeply to understand an author they care about, is an avenue to build the hermeneutic skills that make product organizations thrive.

Narrative Detail Helping with Feedback and Coaching

It’s table stakes that narrative helps get early funding and sales at a startup, in particular for founders who lack product specificity and have nothing to sell but an idea (and their charisma, network, and reputation). But the constraints of the pitch deck genre are so formulaic that humanities training may be a crutch, not an asset, to succeeding at creating them. Indeed, anyone versed in narratology (the study of narrative structure) can easily see how rigid the pick deck genre is, and anyone with creative impulses will struggle to play by the rules.

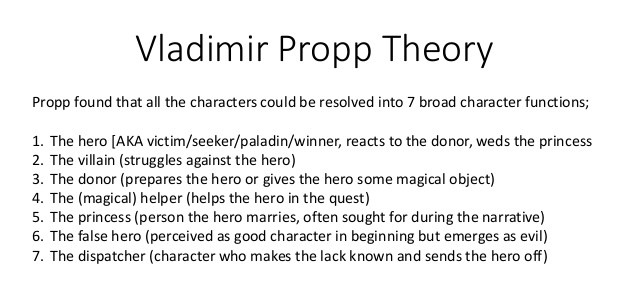

I first understood this while attending a TechStars FinTech startup showcase in 2016. A group of founders came on stage one by one and gave pithy pitches to showcase what they were working on. By pitch three, it was clear that every founder was coached to use the exact same narrative recipe: describe the problem the company will address; imagine a future state changed with the product; sketch the business model and scope out the total addressable market; marshal biographical details to prove why the business has the right team; differentiate from competitors; close with an ask to prospective investors. By pitch nine, I had trouble concentrating on the content beyond the form. It reminded me of Vladimir Propp’s Morphology of the Folktale.

This doesn’t mean that storytelling isn’t part of technology startup lore. It is. But the expectations of how those stories are told is often so constrained that rigorous humanities training isn’t that helpful (and it’s downright soul-destroying to feel forced to adopt the senseless jargon of most tech marketing). In my experience, narrative has been more poignant and powerful in a different area of my organizational life: coaching fellow employees through difficult interpersonal situations or life decisions.

A first example is the act of giving feedback to a colleague. There are many different takes on the art of making feedback constructive and impactful, but the style that resonates most with me is to still all impulses towards abstraction (“Sally is such a control freak!”) and focus on the details of a particular action in a particular moment (“In yesterday’s standup, Sally interrupted Joe when he was overviewing his daily priority to say he should do his task differently than planned.”). As I described in a former post, what sticks with me most from my freshman year Art History 101 seminar was learning how to overcome the impulse towards interpretation and focus on observing plain details. When viewing a Rembrandt painting, everyone defaulted to symbolic interpretation. And it took work to train our vision and language to articulate that we saw white ruffled shirts and different levels of frizziness in curly hair and tatters on the edges of red tablecloths and light emanating on from one side of the painting. It’s this level of detailed perception that is required to provide constructive feedback, feedback specific enough to enable someone to isolate a behavior, recognize it if it comes up again, and intentionally change it. When stripped of the overtones of judgment (“control freak!”) and isolated on the impact behavior has had on others (“after you said that, Joe was withdrawn throughout the rest of the meeting”), feedback is a gift. Now, no training in art history or literature prepares one to brace the emotional awkwardness of providing negative feedback to a colleague. I think that only comes through practice. But the mindset of getting underneath abstraction to focus on the details is certainly a habit of mind cultivated in humanities courses.

A second example is in relating something from one’s own experience to help another better understand their own situation. Not a day goes by where a colleagues doesn’t feel frustrated they have to do task they feel is beneath them, anxious about the disarray of a situation they’ve inherited, confused about whether to stay in a role or take a new job offer, resentful towards a colleague for something they’ve said or done, etc… When someone reaches out to me for advice, I still impulses to tell them what to do and instead scan my past for a meaningful analogue, either in my own experience or someone else’s, and tell a story. And here narrative helps. Not to craft a fiction that manipulates the other to reach the outcome I want him or her to reach, but to provide the right framing and the right amount of detail to make the story resonate, to provide the other with something they can turn back to as they reflect. Wisdom that transcends the moment but can only be transmitted in full through anecdote rather than aphorism.

Leadership Communication

I’ll close with an example of an executive speech act that humanities education does not help prepare for. A constructive and motivating company-wide speech is, at least in my experience, the hardest task executives face. Giving an excellent public speech to 2000 people is a cakewalk in contrast to giving a great speech about a company matter to 100 colleagues. The difficulty lies in the kind of work a company speech does.

The work of a public speech is to teach something to an audience. A speaker wants to be relevant, wants to know what their audiences knows and doesn’t know, reads and doesn’t read, to adapt content to their expectations and degree of understanding. Wants to vary the pace and pitch in the same way an orchestra would vary dynamics and phrasing in a performance. Wants to control movement and syncopate images and short phrases on a slide with the spoken word to maximally capture the audiences’ attention. There are a lot of similarities between giving a great university lecture and giving a great talk. This doesn’t mean training in the humanities prepares one for public speaking. On the contrary, most humanists read something they’ve written in advance, forcing the listener to follow long, convoluted sentences. Training in the humanities would be much more beneficial for future industry professionals if the format of conference talks were a little more, well, human.

The work of a company speech is to share a decision or a plan that impacts the daily lives and sense of identity of individuals that share the trait that, at this time, they work in a particular organization. It’s not about teaching; the goal is not to get them to leave knowing something they didn’t know before. The goal is to help them clearly understand how what is said impacts what they do, how they work, how they relate to this collective they are currently part of, and, hopefully, to help them feel inspired by what they are asked to accomplish. Unnecessary tangents confuse rather than delight, as the audience expects every detail to be relevant and cogent. Humor helps, but it must be tactfully displayed. It helps to speak with awareness of different individuals’ predispositions and fears: “If I say this this way, Sally will be reminded of our recent conversation about her product, but if I say it that way, Joe will freak out because of his particular concern.” People join and leave companies all the time, and a leader has to still impulses towards originality to make sure newcomers hear what others have heard many times before without boring people who’ve been in the company for a while. The speech that resonates best is often extremely descriptive and leaves no room for assumption or ambiguity: one has to explicitly communicate assumptions or rationale that would feel cumbersome in most other settings, almost the way parents describe every next movement or intention to young children. At the essence of a successful company talk is awareness of what everyone else could be thinking, about the company, about themselves, and about the speaker, as one speaks. It’s a funhouse of epistemological networks, of judgment reflected in furrowed brows and groups silently leaving for coffee to complain about decisions just after they’ve been shared. It’s really hard, and I’m not sure how to train for it outside of learning through mistakes.

What This Means for Humanities Training

This post presented a few examples of how habits of mind I developed in the humanities classroom helped me in common tasks in industry. The purpose of the post is to reframe arguments defending the value of the humanities from knowledge humanists gain to the ways of being humanists practice. Without presenting detailed statistics to make the case, I’ll close by mentioning Christian Madsbjerg’s claim in Sensemaking that humanities students may be best positioned for non-linear growth in business careers. They start off making significantly lower salaries than STEM counterparts, but disproportionately go on to make much higher salaries and occupy more significant leadership positions in organizations in the long run. I believe this stems from the habits of mind and behavior cultivated in a rigorous humanities education, and that we shouldn’t dilute it by making it more applicable to business topics and genres, but focus on articulating just how valuable these skills can be.

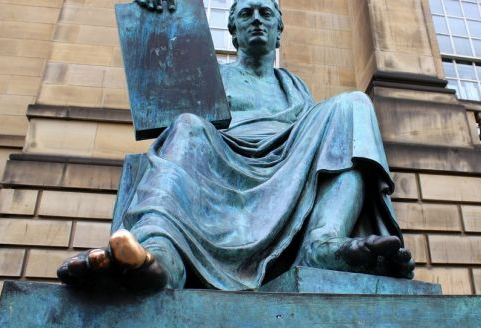

The featured image is of the statue of David Hume in Edinburgh. His toe is shiny because of tourist lore that touching it provides good fortune and wisdom, a superstition Hume himself would have likely abhorred. I used this image as the nice low-angle shot made it feel like a foreboding allegory for the value of the humanities.