I did my first TED Talk in October, part of a TED Salon in New York City. I’ve thanked Alex Moura, TED’s technology coordinator, for inviting me and coaching me through the process, but it never hurts to say thanks multiple times. I’d also like to extend thanks to Cloe Sasha, Crawford Hunt, Corey Hajim, and the NYC production and makeup crew. As I wrote about last summer, stage crews are pre-talk angels that help me metabolize anxiety through humor, emotion, and the simple joy of connecting with another individual. At the TED headquarters, the crew gave me a detailed run down of how the audio and video systems work, how they edit raw recordings, how different speakers behave before talks, and why they decided to be in their field. I learned something. I can precisely recall how the production manager laced his naturally spindly, Woody-Allenesque voice with a practiced hint of care, cradling the speakers with confidence before we took the stage. His presence exuded joy through focused concentration, the joy of a professional who does his work with integrity.

Here’s the talk. My hands look so theatrical because I normally release nervous energy as kinetic energy by pacing back and forth. TED taught me that’s a chump move that distracts the audience: a great presenter stays put so people can focus. The words, story, tone, pitch, dynamics, emotions, and face cohere into an impression that draws people in because multiple parts of their brain unite to say “Pay attention! Valuable stuff is coming your way!”[1] I have some work to do before I master that. When I gave the talk, my mind’s albatross meta voice was clamoring “Stay put! Resist the urge! Stop doing that! In channel 8 you’re at chunk 3 of your AI talk right? Enter spam filter to illustrate the difference between Boolean rules and a learned classifier…what’s that person in row 2 thinking? Is the nod…yeah, seems ok but then again that eyebrow…interference from channel 18 your fucking vest isn’t hooked…shit…” resulting in moments in my talk where my gestures look like moves from Michael Jackson’s Thriller.[2] Come to think of it, I’m often appalled by the emotions my face displays in snapshots from talks. Seeing them is stranger than hearing the sound of my voice on a recording. My emotional landscape shifts quickly, perhaps quickly enough that the disgust of one femtosecond resolves into content in the next, keeping the audience engaged as time flows but leading to alien distortions when time freezes.

As I argued in my dissertation (partially summarized here), I’m a fan of Descartes’ pedagogical opinion that we learn more from understanding how someone discovered something-and then challenging ourselves to put this process into practice so we can come to discover something on our own-than we do from studying the finished product. I therefore figured it may be useful for a few readers if I shared how I wrote this talk and a few of the lessons I learned along the way.

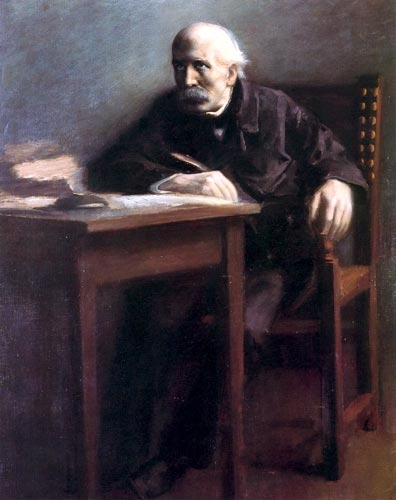

Like Edgar Allen Poe in his Philosophy of Composition, I started by thinking about the intention of my talk. Like Poe, I wanted to write a talk “that should suit at once the popular and the critical taste.” This was TED, after all, not an academic lecture at the University of Toronto. I needed an introduction to AI that would be accessible to a general audience but had enough rigor to merit respect from experts in the field. I often strive to speak and write according to this intention, as I find saying something in plain old English pressure tests how well I understand something. Poe then talks about the length of a poem, wanting something that can be read in one sitting. Most of the time, the venue tells you how long to speak, and it’s way harder to write an informative 10-minute talk than a cohesive 45-minute talk. TED gave me a constraint of 12 minutes. So my task was to communicate one useful insight about AI that could change how a non-expert thinks about the term, to shows this one insight a few different ways in 12 minutes, and to do this while staving off the inevitable grimaces from experts.

Alex and I started with a brief call and landed, provisionally, on adapting a talk I gave at Startupfest in 2017. The wonderful Rebecca Croll, referred by the also wonderful Jana Eggers, invited me to speak about the future of AI. As that’s just fiction, I figured I’d own it and tell the fictional life story of one Jean-Sebastian Gagnon, a boy born the day I gave my talk. The talk pits futurism alongside nostalgia, showing how age-old coming-of-age moments, like learning about music and falling in love, are shaped by AI. He eventually realizes I’m giving a talk about him and intervenes to correct errors in my narrative. Alex suggested I adapt this to a business applying AI for the first time. I was open to it, but didn’t have a clear intuition. It sat there on the back burner of possibility.

The first idea that got me excited came to me on a run one morning through the Toronto ravines. The air was crisp with late summer haze. Limestone dust bloomed mushroom clouds that hovered, briefly, before freeing the landscape into whitewashed pastel. The flowers had peaked, each turgid petal blooming signs of eminent decay. Nearby a woman with violet grey hair that matched the color of her windbreaker and three-quarter length leggings used her leg strength to hold back a black lab who wanted nothing more than to run beside me down the widening path. With music blaring in my ears, I was brainstorming different ideas and, unsurprisingly, found myself thinking about an anecdote I frequently use ground the audience’s intuitions about AI when I open my talks. It’s a story about my friend Andrew bootstrapping a legal opinion from a database of former law student responses (I wrote about here and used to open this talk). I begin that narrative with a reference to Tim Urban’s admirable talk about procrastination. And, suddenly it hit: a TED talk within a TED talk! Recursion, crown prince of cognitive delight. “OMG that’s it! I’ll generate a TED talk by training a machine learning model on all the past TED talks! Evan Macmillan’s analysis of word frequency in all the former Data Driven talks worked well. Adapt his approach? Maybe. Or, I can recount the process of creation (meta reference not intended) to show what happens when we apply AI: show the ridiculous mistakes our model will make, show the differences between human and machine creation, grapple with the practical tradeoffs between accuracy and output, and end with a heroic message about a team bridging the different ways they see the same problem to create something of value. Awesome!” I called my parents, thrilled. Wrote slack messages to engage two of my colleagues. They were thrilled. We were off the to races, pushed by the adrenaline of discovery amplified by the endorphins of a morning run.

The joy of my mind racing, creating at a million miles an hour, provided uncanny relief. It was one of the first morning runs I’d taken in a while, after experimenting over the summer with schedule that prioritized cognitive output. As my mind is clearest between 6:00-10:00, I got to the office before 6:30 am and shifted exercise to the afternoons or evenings. I didn’t neglect my body, but deprioritized taking care of it. And in doing so, I committed the cardinal sin of Western metaphysics, fell into the Cartesian trap I myself tried to undo in my dissertation! The mistake was to think of the mind and its creations as independent from the body. Feeling my creativity surge on that morning run hit home: I thought in a way I hadn’t for months. I’ve since changed my schedule, and do make time for creative work in the morning. But I also exercise. It fuels my coherence and my generative range, the two things I value most.

I wrote to Alex at TED to tell him about my awesome idea. He was like, “yeah it’s cool, but we don’t have enough time to do that. Can you send me a draft on another topic so we can iterate together asap?”[3]

Hmpf.

Back to the drawing board.

Now, having a day job as an executive, I don’t have a lot of time to write my talks. I’ve perfected the art of putting aside two or three hours just before I have to give a presentation to tailor a talk to an audience. These kinds of constraints empower and fuel me. They don’t leave enough time for the meta critical voices to pop up and wave their scary-ass Macbeth brooms in my mind. I just produce. And, given the short time constraints, I never write my talks. Instead, I write the talk equivalent of a jazz scaffold, with pictures like a chord series upon which the musicians improvise. My talk’s logic is normally partitioned into phrases, stanzas, chunks. Another way to think about the slides are like the leitmotifs bards used in oral poetry, like the “rosy-fingered dawn” we see pop up in Homer. And I’ve done this, with reward feedback loops, for a few years. It’s ossified into a method.

A TED talk isn’t jazz. It’s like a classical concerto. You write it out in advance, practice it, and execute the harmonics, 16th notes, and double stops with virtuosic precision (I’m a violinist, so these are kinds of things I worry about). You rehearse, you don’t improvise.

That challenged me in a few ways.

First, breaking my habits spurred the nervousness we feel when we learn how to do something new. When I sat down to write a draft, my head went into talk writing mode. I did what I always do: started with an anecdote like the Andrew story, composed in chunks, represented the chunks with mnemonic devices in the form of random pictures that mean something to me and me only (until the audience sees the humorous, synthetic connection to the content). I booked an hour in my calendar to make progress on a draft but that was it: I had to move on and deliver the outcomes I’m responsible for as an executive. I just couldn’t prioritize the talk yet. So the anxiety would arise and fester and fuel itself on the constraints. I’d cobble together a few pictures and some quick notes and send them to the TED team and some friends who wanted to help review, knowing what I was sending was far from decent and near to incomprehensible.

For, of course, they couldn’t make heads or tails of the random pictures that work at a different level of meaning than the talk itself. They’d respond with compassion, do their best to gently communicate their befuddlement. It was humorously bad. And every time they expressed confusion, it eroded my confidence in the foundation of the talk. I felt a need to start over and find a new topic. I face communication foibles like this in other areas of my life and, as I work to be a better leader, try to make the time to think through the perspectives of those receiving a communication before I send it. I imagine other artists or former academic face similar challenges: we are used to prizing originality, only writing or saying something if it hasn’t been said before. In business, there’s value in repetition: saying something multiple times to increase the probability that people have heard and understood it, saying the same thing different ways in different genre and for different audiences, teaching everyone in the company to say the same thing about what you do so there is unity of message for the market. It’s against my instincts, require vigilance to preserve predictability for my teams and consistency for the market. Even for my TED talk, I felt a need to say something new. To titrate AI to its very essence, to its extraordinary quintessence. Some people coaching me said, “no, darling, they just want you to say what you’ve said a million times before. You say it so well.”

Finally, I wasn’t used to rehearsing, sharing drafts, or exposing the finished product outside the act of performance. There are two sub-points here. The first has to do with the relative comfort different people have in exposing partial ideas to others. I’m all for iteration, collaboration, getting feedback early to save time and benefit from the possible compounded creativity of multiple minds. But, as an introvert often mistaken to be an extrovert and someone trained in theoretical mathematics, I feel at ease when I have time to compose compound thoughts, with deliberately ordered, sequential parts, before sharing them with others. Showing a part is like starting a sentence and stopping midway. Not sharing early enough or quickly enough is another foible I have to constantly overcome to fit into tech culture; I believe many introverts feel similarly. Next, the pragmatic and performative context of the speech act changes it. As mentioned above, I’m a violinist, so have rehearsed and then performed many times before. But I don’t rehearse talks and really only have to myself as audience, repeating turns of phrase out loud until they hit the pithy eloquence I prize. What I didn’t know how to do was to rehearse before others. And it’s a hell of a lot harder to give a talk to one person than it is to an audience. It’s as if my self gets turned inside out when I give a talk to a single observing individual. I feel the gaze. Project what I suspect they see into a distorted clown mirror. It’s like a supreme act of objectification, all men’s eyes gazing intently on the body of Venus. Naked. Bare. Exposed. It’s 50,000 times easier to give a speech to an audience, where each individual becomes a part of an amorphous crowd, enabling me, as speaker, to speak to everyone and no one, focusing on the ideas while also picking up the emotional feedback signals acting on a different level of my brain. Learning how to collaborate, how to overcome these performative fears, was useful and something I’ll carry forward.

Midway upon this journey, finding myself within a forest dark, having lost the straightforward pathway, I came across the core idea I wanted to communicate: to succeed with AI, businesses have to invert the value of business processes from techniques to reduce variation/increase scale to techniques to learn something unique about the world that can only be learned by doing what they do. Most people think AI is about using data to enhance, automate, or improve an existing business process. That will provide sustaining innovation, but isn’t revolutionary. Things get interesting when existing products are red herrings to generate data that can create whole new products and business lines.[4] I liked this. It was something I could say. I could see the work of my talking being to share a useful conceptual flip. My friend Jesse Bettencourt helped formulate the idea and sent me this article about Google Maps as an example of how Google uses products and platform to generate new data. I sat down to read it one Saturday and footnote six caught my attention:

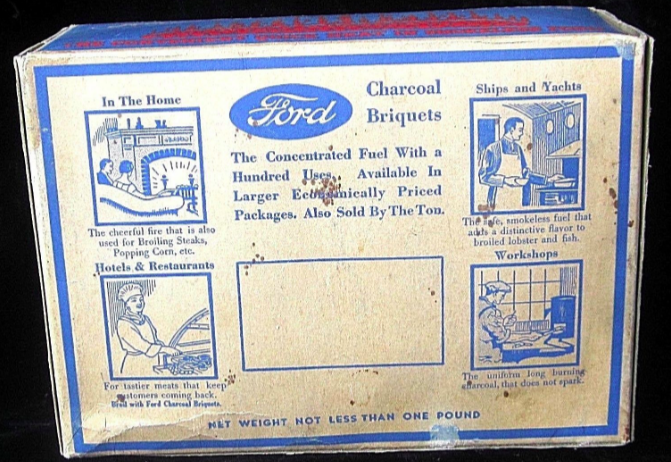

I loved the oddness of the detail. And the more I searched, the stranger it got. Thomas Edison helped Henry Ford started a charcoal production facility after he had too much wood from the byproduct of his car business? Kingsford charcoal was a spinoff, post acquisition by Clorox, of a company founded by Henry Ford? Henry Ford pulled one of those oblique marketing moves like the Michelin Brothers, using the charcoal businesses to advertise the wonderful picnics that waited at the end of a long car ride to give people somewhere to drive to?[5] It gripped me. Provided joy in telling it to others. I wanted people to know this. Gripped me enough that it became almost inevitable that I begin my talk with it. After all, I needed a particular story to ground what was otherwise an abstract idea. I go back and forth on my opinion of the Malcolm Gladwellian New Yorker article, which I (potentially erroneously, as I am not Gladwell expert) structure as:

- Start with an anecdote that instantiates an abstract idea

- Zoom out to articulate the abstraction

- Show other examples of the abstraction

- Potentially come back to unpack another aspect of the abstraction

- Give a conclusion people can remember

This is more or less how my talk is structured. I would have loved to use a whole new form, pushing the genre of the talk to push the boundaries of how we communicate and truly lead to something new. All in due time.

Even after finding and getting excited about Henry Ford, I prevaricated. I wasn’t sure if the thesis was too analytical, wasn’t sure if I wanted to use these precious 12 minutes to show the world my heart, not my mind. There was a triumphant 40 or so hours where I was planning to tell the world’s most boring story from the annals of AI, a story about a team at a Big Four firm that builds a system to automate a review of the generally acceptable accounting principles (GAAP) checklist. I liked it because it’s moral was about teams working together. It showed that real progress with AI won’t be the headlines we read about, it will be the handwritten digit recognition systems that made the ATM possible, the natural language processing tools that made the swipe type on the Android possible. Humble tools we don’t know about but that impact us every day. This would have been a great talk. Aspects from it show up in many of my talks. Maybe some day I’ll give it.

In the end, I never actually wrote my TED talk. I told people I was memorizing an unwritten script. For me, the writing you read on this blog is a very different mode of being than the speaking I do in talks. The acts are separate. My mind space is separate. So, I gave up trying to write a talk and went back to my phrases, my chunks. Went back to rehearsing for an invisible audience. I walked 19 miles up the Hudson River on the day I gave my talk. I had my AirPods in and pretended I was talking on the phone so people didn’t think I was crazy. I suspect I needed the pretense to cushion my concentration in the first place. It was a gorgeous day. I took photos of ships and docks and branches and black struts and rainbow construction cones in bathroom entrances. I repeated sentences out loud again and again until I found their dormant lyricism. I practiced my concerto by myself. And then, I practiced in front of my boyfriend in the hotel room one last time before the show. He listened lovingly, patiently, supportively. He was proud. I felt comfortable having him watch me.

I pulled off the performance. Had a few hiccups here and there, but I made it. I reconnected with Teresa Bejan, a fellow speaker that evening and a former classmate from the University of Chicago. I did one dress rehearsal with my team at work and will always remember their keen attention and loving support. And I found a way to slide my values, my heart, into the talk, ending it with a phrase that encapsulates why I believe technology is and always will be a celebration of human creativity:

Machines did not see steaming coffee, grilled meats and toasted sandwiches in a pile of sawdust. Humans did. It’s when Ford collaborated with his teams that they were able to take the fruits of yesterday’s work and transform it into tomorrow’s value. And that’s what I see as the promise of artificial intelligence.

[1] In Two lessons from giving talks, I explained why having the AV break down two thirds of the way into a talk may be a hidden secret to effective communication. It breaks the fourth wall, engaging the audience’s attention because it breaks their minds’ expectation that they are in “listen to a talk” mode and engages their empathy. When this has happened to me, the sudden connection with the audience then fuels me to be louder and more creative. We imagine the missing slides together. We connect. It’s always been an incredibly positive feedback loop.

[2] Michael Jackson felt the need to “stress”, at the beginning of the Thriller music video, that “due to his strong personal convictions, [he wishes] to stress that [Thriller] in no way endorses a belief in the occult.” It’s worth pausing to ask how it’s possible that someone could mistake Thriller as a religious or cult-like ritual, not seeing the irony or camp. The gap between what you think you are saying and what ends up being hard never ceases to amaze me. It’s bewilderingly difficult to write an important email to a group of colleagues that communicates what you intend it to communicate, in particular when emotions and selective information flow and a plurality of goals and intentions kicks in. One of my first memories of appreciating that acutely was when people commented on a 5-minute pitch version of my dissertation I gave at the Stanford BiblioTech conference in 2012. One commenter took an opinion I intended to attribute to Blaise Pascal as something I endorsed at face value. I thought I was reporting on what someone else thought; the other heard it as something I thought. These performative nuances of meaning are crucial, and, I believe, a crucial leadership skill is to be able to manage them as a virtuosic novelist manages the symphony of voices and minds in the characters of her novel. This is one of the many reasons that we need to preserve and develop a rigorous humanistic education in the 21st century. The nuances of how humans make meaning together will be all the more valuable as machines take over more and more narrow skills tasks. Fortunately, the quantum entanglement of human egos will keep us safe for years to come. I’d like to resurrect programs like BiblioTech. They are critically important.

Side note 2. In May, 2005, an old Rasta, high as a kite, told me at the end of a hike through a mountain river near Ocho Rios that I looked like Michael Jackson, presumably towards the end of his life when his skin was more white. That was also a bizarre moment of viewing myself as others view me.

[3] Alex also told me about an XPRIZE for an AI-generated TED talk back in 2014. Also, my dear friend and forever colleague Dan Bressler came up with the same idea down the line and we had a little moratorium eulogizing a stillborn.

[4] Andrew Ng has shared similar ideas in many of his talks about building AI products, like this one.

[5] The Michelin restaurant guide, in my mind, predated the contemporary fad of selling experiences rather than products. Imagine how difficult it would be to market tires. A standard product marketing approach would quickly bore of describing ridges and high-quality rubber. But giving people awesome places to drive to is another story. I think it’s genius. Here’s a photo of an early guide.

The featured image is of an unopened one-pound box of Ford Charcoal Briquets, dating back to 1935-37 and available for purchase on WorthPoint, The Internet of Stuff TM. Seller indicates that she does “not know if briquettes still burn as box has not been opened.” The briquettes were also son by the ton. Can you imagine a ton of charcoal? One of my favorite details, which made its way into my talk, is that a “modern picnic” back in the 1930s featured “sizzling broiled meats, steaming coffee, and toasted sandwiches.” The back of the box marketed more of the “hundred uses” of this “concentrated source of fuel”: to build a cheerful fire in the home (also useful for broiling steak and popping corn), to add a distinct flavor to broiled lobster and fish on boats and yachts without smoking up the place, to make tastier meats in restaurants that keep customers coming back. I find the particularity of the language a delightful contrast to the meaninglessness of the language we fill our brains with in the tech industry, peddling jargon that we kinda think refers to something but that we’re never quite sure refers to anything except the waves of a moment’s trend. Let’s change that.