You might prefer to read the second part of this post first. It will seem more familiar, as its I is closer in voice and referent to the I in other posts on this blog. Or, you might prefer to read the first part first and see how you feel.

It became possible when I noticed him noticing the quick assuredness of Agilulf’s hands arranging pine cones in an isosceles triangle at dawn. It was one of the early moments where he identified completely with nonexistent knight. Where they shared a feeling. Where his need to feel in Agilulf a presence more solid and concrete than the other paladins was met with and mirrored by Agilulf’s own need to count objects, arrange them in geometric problems, resolve problems of arithmetic, apply himself in any way possible to recover precision into a world faintly touched, just breathed on by light. In that hour in which one is least certain of the world’s existence. I was manically focused on Agilulf at the time, so focused that I was unable to recognize Raimbault’s sensitivity through the mask of his youth. But here, now, having come into my desire, the recollection changes. I am able to see that, had Raimbault not sought solidity, and, what’s more, not questioned this very act of seeking as he started to sense that the tiresome need to tuck himself into a ready-made belief system, a system retrofit with ritual and rules of conduct, might actually signal cowardice, he wouldn’t have felt oppression upon seeing the nonexistent knight counting trees, leaves, stones, lances, pine cones, anything in front of him. There was undeniable kinship when we first met, but it was hoplite kinship, the homoerotic, fraternal bonds Plato describes in the Symposium, the mute community born in battle. I stayed silent. Refrained from speech lest anyone, even he whom I protected, discern my womanhood. I’ve grown accustomed to the dull pain of absconding my identity. It rings in my ears like tinnitus. Reminds me that I will always be excluded because I am a woman. When I first entered the knighthood, I tried to be one with them, to participate in the fraternity that arises when they, we, together, act according to the oaths we have taken as knights. But my path is one of solitude. As woman, I am unable to fulfill their aching needs on the battlefield. I watch how they relive Gilgamesh’s love for Enkidu, recover Achilles’ love for Patroclus, how they seek a mirror self to offset the traits they now know they lack and therefore desperately seek to replenish in another. I can only feel this bond, this mute community, from a place of pretense, by covering my gender, a portion of my identity, so they see what they need see and so I can continue doing what I was born to do. What I love. This is where Raimbault, at first, was so mistaken. He reduced me to a caricature, assumed, because of the excellence of my practice, that I existed, that I was definite. He couldn’t grasp that what I sought was an entirely different way of existing, one that reached the apotheosis of form in the form only embodied by the nonexistent knight. That the vagaries of men tired me. Their slothfulness. Their corpulence. Their farts and burps. I wanted more. Would go so far as to enter a nunnery to learn the dark arts of sublimation, of esteeming the permanent above the fleeting joys of the world. It was a bold act of autonomy, a clamoring for existence so that I no longer had to endure the alienation. In retrospect, I’ve come to feel pity for Charlemagne. Like me, he has been rendered myth. Like mine, his story has been written and rewritten so many times. My entrance into the narrative space of play was set in stone epics ago, imprinted on sandstone by Virgil and twisted, like a variation on a musical theme, through Ariosto and Tasso. The Christians fight the Moors (or the Greeks the Turks, or the Romans the Celts). The damsel comes, our virgin Sophronia. She is abducted and flown on a hippogriph through farfetched twists and turns of fortune to a dragon’s den, her virginity kept sacrosanct so the knights have their way. Her skin is white as lilies, her hair long and flowing like the Nile for the privileged one (few?) who see it free from diadems and braids. And in the heat of battle, just when a hero is about to meet his fate at the brutal swords of the Moors, I appear, a man. I appear with mastery and skill, brandishing the enemy to save the hero. He then seeks me to express gratitude to his kin. But, of course, I’ve disappeared, to the riverside to wash my wounds and calves. When he stops looking (and, concomitantly, the reader has forgotten), he finds me. And discovers, what ho!, that I’m a woman. And since I’ve already forgone the stereotypes of that define my gender, so too might I forgo the innocence of idealized sexuality. At least in the freer times of Ariosto, I am naturally also the representation of homoerotic desire. The voice of the oppressed. For everyone who reads, including the knights, want nothing more than to watch as another, a woman, caresses my milk white breasts. And that is precisely why my path is solitary. Why I had no authentic place on the battlefield. Why, tired of this narrative, I entered the convent to subvert it. This time playing a different female role, that of a nun, of Sister Theodora of the order of Saint Colomba. But even here I found myself caught in a new nexus of alienation, bearing the weight of my elected verisimilitude. For what would a nun, who has no experience apart from religious ceremonies, triduums, novenas, gardening, harvesting, vintaging, whippings, slavery, incest, fires, hangings, invasion, sacking, rape and pestilence, know of battle and knighthood? Nothing. Of battles, I now feign to say, I know nothing. I must rid myself of my past precisely as I go about reconstructing it in my tale. But perhaps it is this distancing from my past that grants me freedom to create a new future? Perhaps it is this distancing that has granted me the ability to create worlds within from a pen stroke act of will, as here on the river’s bank I set a mill, and there, beyond the town I trace out a wood, and in this wood follow Agilulf as he scours it through and through, follow him to Priscilla’s palace where I live my own dream of chaste seduction as the nonexistent knight subverts all direct acts of concupiscence and sexuality. There was a rush to the power. A draw to a newfound ability, to a creativity absconded from the pressures and pulls of others, a place of repose. But I also felt fear at how precarious and coincidental the space available to my imagination turned out to be. One morning, for example, as I was writing I was constantly distracted by the clatter of copper and earthenware as the sisters in my convent washed platters for dinner. It reeked of cabbage. The smells infiltrated me. And when I went back the next day to observe my creation I was appalled to see I’d brought the convent to the book, describing the mess hall and how out of place Agilulf seemed at the feast. The contingent determinism of my environment, of a bunch of nuns making cabbage soup, seemed crass in contrast to the dusty aura of the epics that had grafted my existence before. So I stopped. Wrote more and more quickly. Abandoned the details. Didn’t retain the discipline required to recreate the scene, to help you, reader, live it, feel it, enter it fully. Jumped from France to England, England to Africa, and Africa to Brittany with utter disregard for the Aristotelian rules of time and place. I relaxed the constraint that weighed me down, the discipline of a cohesive third-person chronicle and even went so far as to address the book I was writing in the vocative like I did when I wrote in my journal as a child. Book, I wrote, now you have reached your end. And miraculously, at this moment of abandon and decadence, I heard a horse come up a narrow track. I recognized the voice of Raimbault. And while I’ll never love him ardently, never find in him the elision I seek with another to finally know the world, I know from what I’ve chronicled how much he loves me, how he has loved me since he noticed me peeing in the stream after I saved his life. I’ll rush to meet him, let him guide my pen as life urges along, and mount the crupper of my horse to find my future. Because no one would have expected it. It’s not the plot. Nothing I’d create. It could not be Bradamante. Therein, perhaps, I’ll find the possibility of freedom.

What you’ve just read is an experiment. An attempt to become a better reader.

In the experiment of reading Italo Calvino’s The Nonexistent Knight, this meant a few things.

First, it meant engaging with the text actively-and returning to it a few times in a short time frame-to better register and remember it. This took effort, even emotional effort. Reading literature and philosophy passively is at once an indulgent pastime and an attempt to keep a former self intact and alive, a self who spent most of her time reading books and writing about books, whose job it was to say something about books that no one else had said before.[1] My professional success no longer hangs on my knowledge of literature and the artfulness and ingenuity of my interpretation. I changed. Moved to technology. Strive for excellence according to the standards and conventions of a different social circle and profession. But, pretend though I may, my transition was not a complete epigenetic phase shift. Reading still matters to me. And I experience unnerving discomfort when a passage I read just a week ago, a passage that was so alive and vivid while I was reading it, has disappeared like vapor on a car window or footsteps washed away by the sea. My emotional discomfort, therefore, stemmed partially from self-criticism, frustration that total recall wasn’t a given, didn’t effortlessly arise from passive consumption. It was a recognition that I had work do to, coupled with the desire to keep on doing the same because it was easier. So I had to make it fun. Do something creative. Trick myself into making engagement effortless to silence to lacerations of the superego.

Which lead me to fiction. Writing a companion piece that grappled with the question: who is the narrator of The Nonexistent Knight? I’d engage with the book by replicating it, adapting it, making it my own by assimilating it.

This is almost accurate. I actually started by composing a different blog post, one whose I was close in voice and referent to the I in most of my other posts. But I felt too exposed. Projected judgment around the triteness of my conclusions. Felt silly writing a post about trying to remember what I’d read. I needed fiction to protect myself. Needed Bradamante to exorcise my fear. Without her, I wouldn’t feel comfortable writing these words.

Fortunately this cloak of fiction added a layer of reflexivity. The Nonexistent Knight is itself a kind of reading, where, like a medieval artist painting her version of the annunciation or the pietà, Calvino engages with the familiar stories of the Carolingian epics. His writing is a reading of Ariosto, of Tasso, of scenes and memes intimately familiar to his readers. Or at least to some readers. For us, today, there can be no presumption that people know those tales. No awareness of the tradition into which the stories fall. The text doesn’t have a shadow. It lacks the trappings of identity it would have had in a time where it was a given that people know Bradamante, knew Charlemagne, had grown up with the tales. We’re bid to ask what means it means to rewrite a Renaissance Romance in an age when people don’t recognize it’s a recapitulation, but are reading it for the first time. It kaleidoscopes the nonexistence of the protagonist in the text.

And there was more.

Why did I care about becoming a better reader in the first place? What did I seek? Why did my lack of recall create such a rabid sense of discomfort and shame?

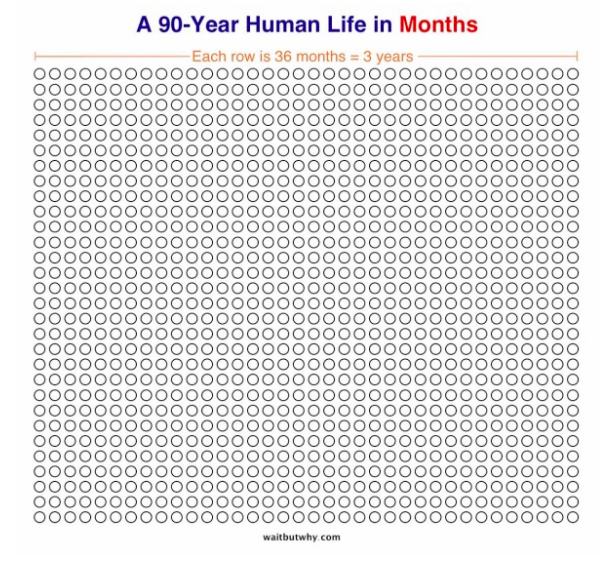

The system of identity Calvino grapples with through the character of the nonexistent knight constitutes selfhood through the embodiment and application of codes of conduct and structures of belief. Knights do X in Y setting; one becomes a knight by passing through Z ritual. Take away a paradigm sanctioned by others’ recognitions that you fit into their code, that you act in a way that confirms how they view themselves, and all that remains is the raw encounter with experience. The constitution of self through and via an amassed collection of experiences. But this self as conversation with the world stands on precariously flimsy stilts unless one can recall with fidelity, unless there is a distancing from the vagaries of momentary subjectivity. In short, it mattered that I could remember things accurately because my very identity was at stake, an identity constituted from a series of encounters and experiences. I wanted, needed, to know the book for what it was, to love it for what it was, so I myself could stand on firmer ground. It’s a lesson I can apply elsewhere, a moral attitude for engaging with the world. An attempt to know the world and its people for what it is and who they are.

One final thought.

There are a few passages in The Nonexistent Knight that I’d remember without all this effort and alienation. The introduction of Gurduloo in chapter three, for example, is hilarious. Gurduloo is the foil of Agilulf, the man who exists but doesn’t think he does as opposed to the man who doesn’t exist but thinks he does. He’s marvelous. Sees ducks and joyfully becomes duck. Sees frogs and mindlessly becomes frog. Sees the king and impudently becomes king. It’s a variation on the joker from an opera di buffa, who speaks the truth no one else can tell. Like Gurduloo to his surroundings, the passages existed without needed to think they existed. They just were. There to be enjoyed without all the reflexive reflection. It feels cliché, but it’s too true not to acknowledge. It’s the bliss of the poet. The ability to be so engaged with the world that it sticks with us and shapes us.

[1] In retrospect, I wish I had been a more dialogical scholar of literature. I admire how my Stanford colleague Harris Feinsod, now a professor at Northwestern, wrote articles in response to and in dialogue with other active literary critics. Responding to someone wasn’t on my mind when I was a graduate student. I engaged with secondary literature, engaged with others’ ideas about the text I was working on, but felt I was arguing with an absent ideal rather than a person.

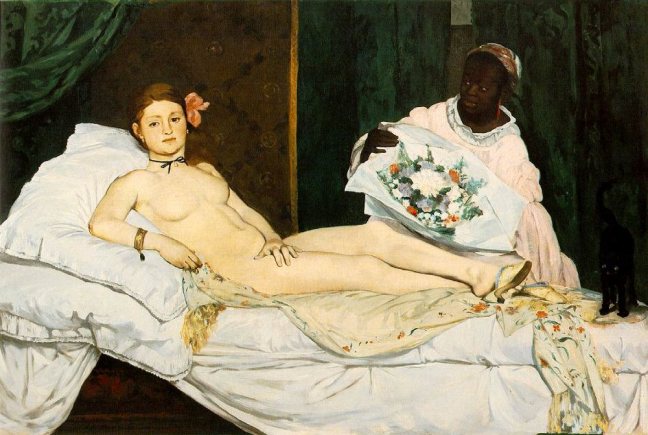

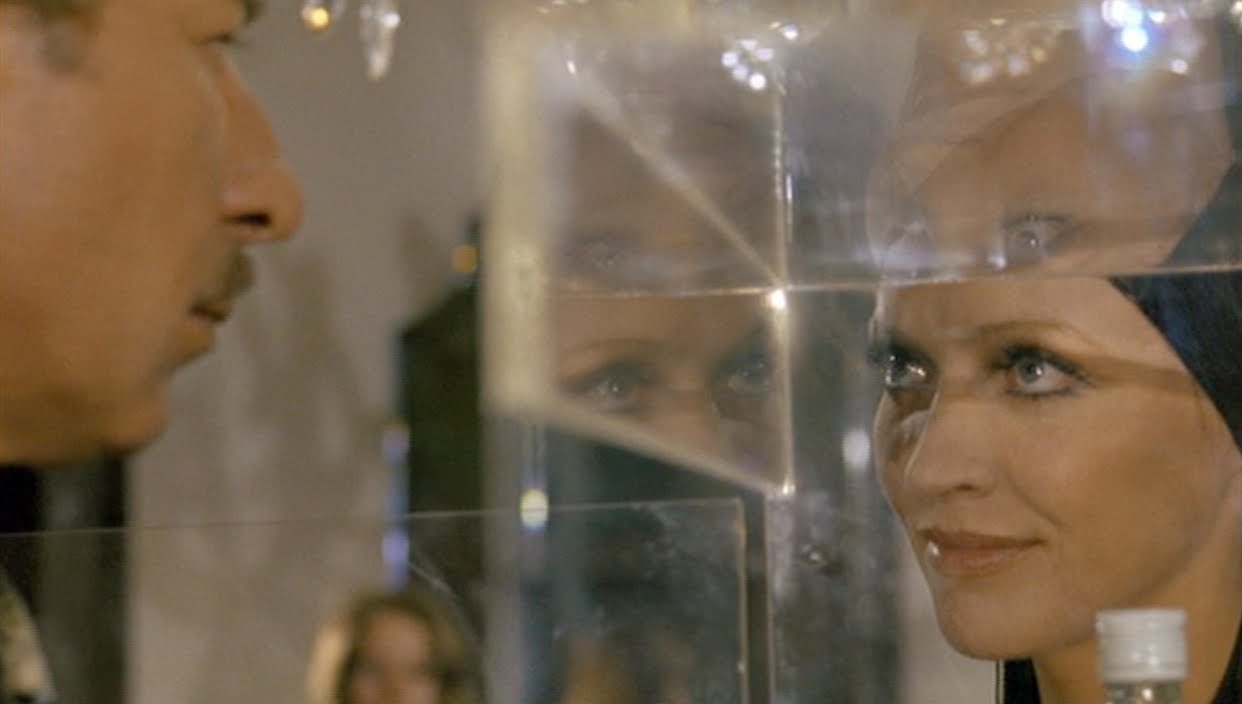

The featured image is from Pino Zac’s 1971 film adaptation of Italo Calvino’s The Nonexistent Knight. I presume (because I only skimmed the film) the man with his arms raised is the King of the Grail, who abdicates the moral weight and responsibility of killing innocent people in the name of fanaticism, which is too often guised as perverse form of Enlightenment. It is a paragon B film, weaving technicolor, black and white, and animation to visually represent the different ontological levels Calvino sculpts in the book (Agilulf and Raimbault as real characters in color; Charlemagne and the other knights as animations; Sister Theodora, the author of the work, imprisoned in her penance of black and white). My partner Mihnea found its style to be unmistakably in the tradition of Federico Fellini. I saw hints of Alejandro Jodorowsky. It’s a fascinating artifact. I’m glad it exists.